Can Robusta even be considered specialty coffee? Coffee expert Constantin Hoppenz argues for a resounding yes, presents compelling arguments, and challenges coffee roasters.

Is Robusta the bad Arabica? This suspicion persists; we hear it in almost every other beginner's course. Our longtime friend, Constantin Hoppenz, has given this a detailed account.

Robusta, a specialty?

When you hear the word Robusta , you usually think of something bad. Associations range from dark, Italian coffee blends with a strong bad breath potential to mass production in Vietnam for instant coffee and other cheap products.

The current picture is clear: Arabica is a must for those who want quality in their cup; Robusta is for those who want it affordable and simple.

Accordingly, most people in the specialty coffee industry have a decidedly negative attitude toward Robusta. Understandably so. If you taste a standard-quality Robusta once, it won't exactly bring a smile to your face.

But why? Is Robusta really as bad as its reputation suggests? What role does Robusta play in the future of coffee? And is there such a thing as specialty Robusta coffee?

Why we should focus more on Robusta. A plea.

Facts for coffee beginners

The botanical name for Robusta is Coffea canephora, which, unlike Arabica (Coffea arabica), is not used. Robusta production has increased significantly in recent decades. Currently, 40% of global coffee production comes from Robusta cultivation (39 million bags). In 1990, the figure was less than half, at 19 million bags. The largest producing countries are Vietnam (40%), Brazil (25%), Indonesia (15%), India (6%), and Uganda (4.5%). Robusta grows best in tropical regions below 1000 meters (Arabica grows better at higher altitudes).

Climate change and economic efficiency

Like any agricultural product, coffee is affected by weather and other natural influences. Coffea arabica is particularly susceptible to fluctuations in temperature and precipitation and also suffers from diseases such as leaf rust.

Around 2014, "la roya" (coffee rust) affected all of Central America, destroying up to 50% of the harvest. Anyone who thinks this is irrelevant to specialty coffee, which grows at high altitudes protected from leaf rust, is far from it. Coffee production is closely intertwined. Sufficient high-quality coffee can only be produced if the coffee-growing countries and their farms are in good health. The vast majority of coffee farmers with specialty coffee make their living by selling average-quality coffee at world market prices.

For coffee-growing countries like Nicaragua, coffee is one of their most important exports. Therefore, preserving this sector is of great importance to these countries. They see an ever-expanding global coffee market, and they want to participate in its growth.

Increasing demand for coffee

By 2050, global demand is expected to rise to as much as 300,000 million bags (currently around 160,000 million). While such figures should be treated with caution, the trend is clear. However, by that time, the agricultural land suitable for Arabica production will be halved due to climate change .

The result would be deforestation to create new agricultural land for Arabica. One possible approach here would be to supplement or replace the Arabica stock with Robusta plants at lower altitudes (below approximately 1,000 meters). The increase in usable coffee would be exponential, as Robusta produces up to four times the yield. In addition, Robusta is far easier to handle and more stable to grow.

Sustainability must also be considered from the producers' economic perspective, because coffee is only grown if it is financially viable. Currently, world market prices for Arabica are below its production costs at just 120 US cents per pound. Added to this are the aforementioned influences of diseases and poor weather conditions, which lead to lower harvest yields. It is therefore not surprising that Robusta is increasingly being viewed as a serious alternative. The Colombian Ministry of Agriculture, in collaboration with Nestlé, recently began testing over 3,000 Robusta seedlings for cultivation. Costa Rica also recently lifted a ban on the production of non-Arabica varieties.

Robusta in research

At the same time, intensive research is producing new Arabica varieties that are significantly more resistant than their predecessors. The CATIE (Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza) research center in Costa Rica alone is investigating over 1,000 new varieties. The genetic diversity of Coffea canephora (Robusta) is of great importance. It is considered the evolutionary parent of Coffea arabica (Coffea canephora + Coffea eugenoides = Coffea arabica), whose genetic material is crucial for the development of resistant Arabicas.

An article published earlier this year entitled “High extinction risk for wild coffee species and implications for coffee sector sustainability” states:

“Robusta coffee has therefore been responsible for overcoming most of the key issues for coffee sector sustainability, either by direct replacement or through use in breeding new cultivars, rendering the development and use of other coffee species unnecessary.”

The article in Science Advances Magazine highlights the threat to naturally occurring coffee species, whose protection is essential for the continued existence of coffee as a crop.

These aspects are therefore directly related to specialty coffee, as they influence almost all regions and producers that produce specialty coffee. Again, specialty coffee is not separate from the ecological challenges and economic hardships of the producers, for whom specialty coffee often represents only a fraction of their income.

A sensory enrichment

From a flavor perspective, Coffea Canephora shouldn't be a no-go either. Anyone who has ever enjoyed a good Robusta knows that it doesn't necessarily have a bitter, bland flavor resembling the smell of car tires. A Fine Robusta , considered a specialty according to the CQI , is just as clean and balanced as a Specialty Arabica.

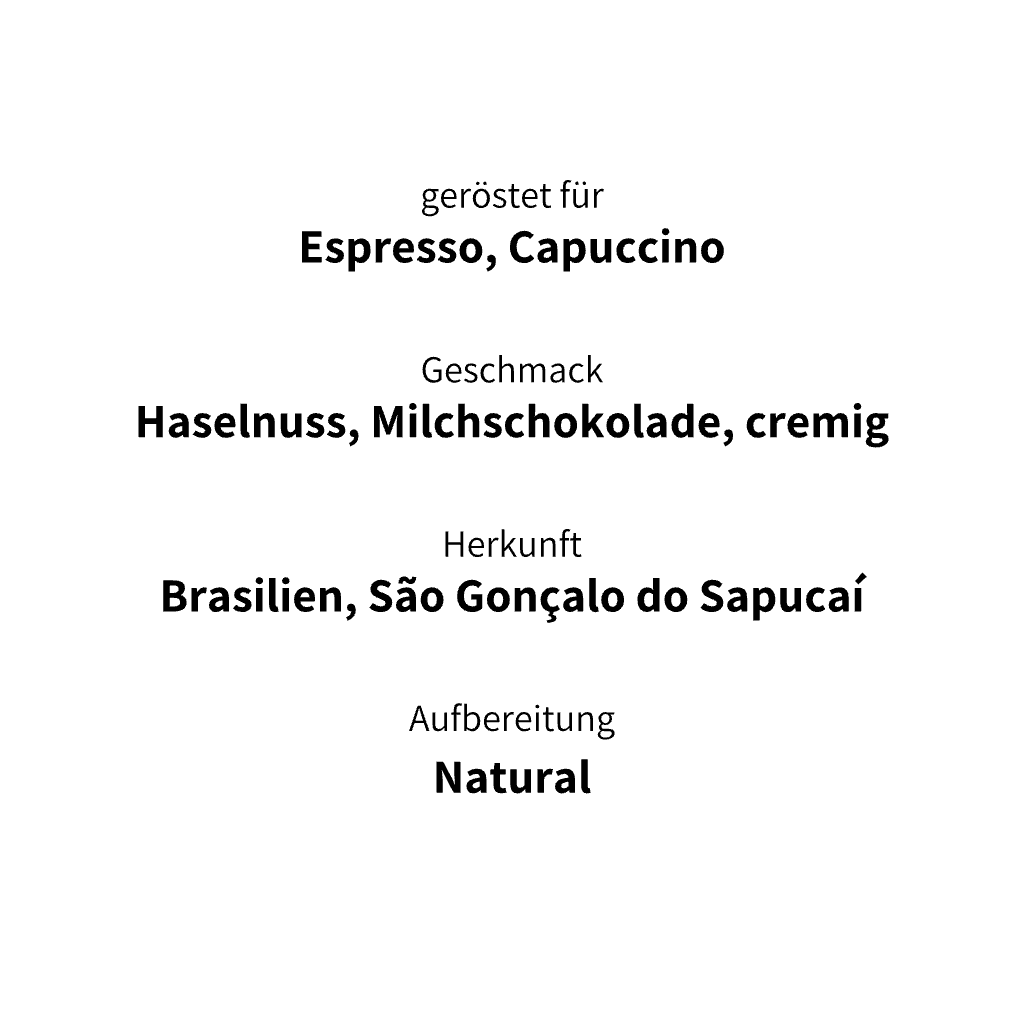

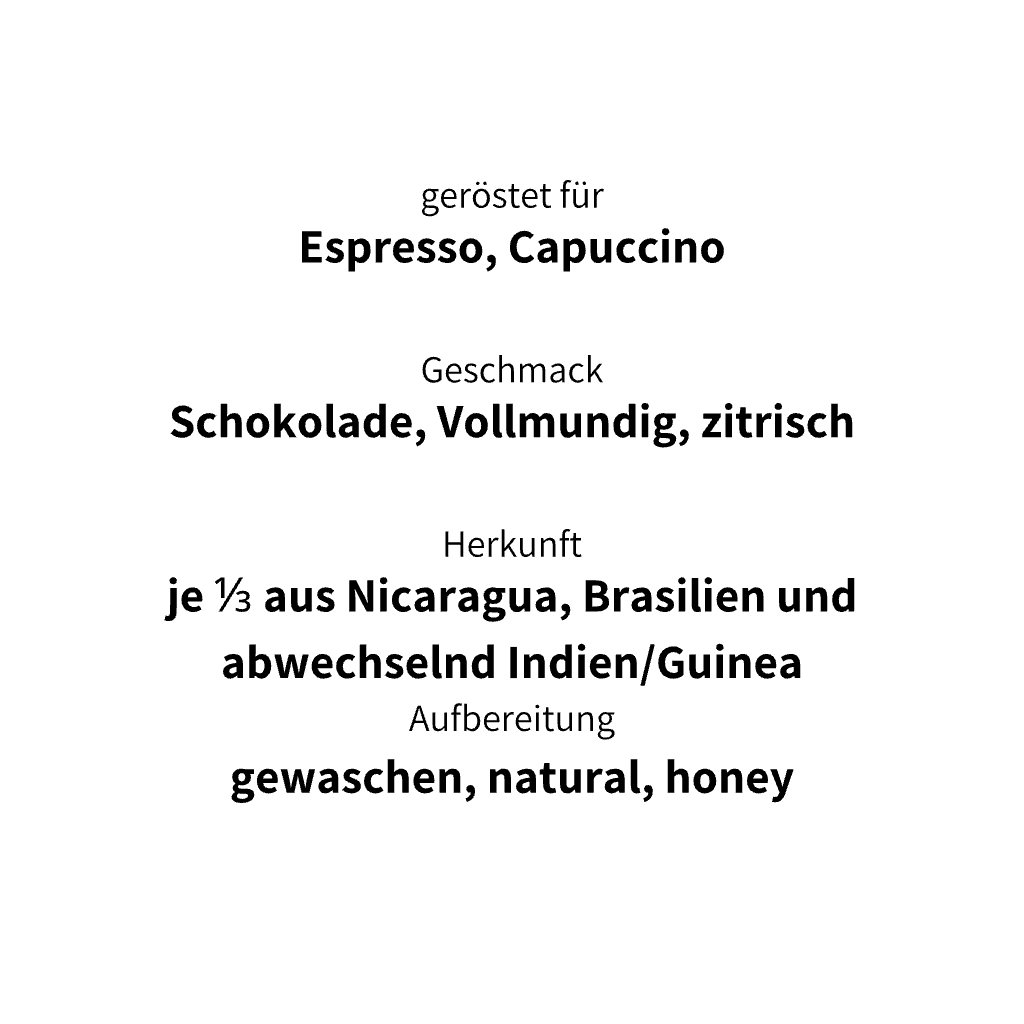

Flavors vary depending on the terroir and processing. They are often nutty and chocolatey, but can also be fruity. A full body is particularly characteristic of Robusta, which makes some Arabicas taste like thin soup. In addition, Coffea canephora has lower perceptible acidity and a higher saltiness, which can be attributed to the higher amount of potassium in the bean (think of the salty caramel flavor).

A higher bitterness is also typical and is caused, among other things, by a higher caffeine content. Up to twice as much caffeine as in Arabica (2–4% vs. 1.5%) is normal. Anyone who struggles to get going in the morning, even after a double espresso (from Arabica), will be pleased. While preferences regarding bitterness vary greatly, as with chocolate, in the right amount, it is sensorially enriching and stimulating.

Where are the specialty Robustas?

If Coffea canephora can be so delicious, why are there virtually no high-quality Robustas to be found in the world's cafés? It has only been recognized for a while that coffee, in general, can be a complex beverage like wine. The term "specialty coffee" first came into circulation in 1974 through a contribution by Erna Knutsen. Since then, a steadily growing number of people have been interested in this unique product. Then as now, driving forces are needed to advance coffee and thus bring about a change in thinking. Until now, there has not been enough stakeholders who would also consider Robusta from a quality perspective to sustainably change its reputation for the better. However, initial efforts were made several years ago. In 2009, the first seminars on the evaluation of Robusta were held under the direction of the Coffee Quality Institute. The goal was to establish a quality standard similar to that for Arabica. A more recent version of this protocol was recently published during the World of Coffee in Berlin. According to this protocol, a Fine Grade Robusta is one that scores at least 80 points and has fewer than 8 defects in a 350g sample.

Some notable farms that already consistently produce Fine Robusta are the Sethuraman Estate in India and the Jhai Cooperative in Laos.

Those who taste Specialty Robusta for the first time often don't even realize it's Robusta. As wonderful as this is, it's important to note that Robusta requires a different approach.

Robusta often loses in comparison with Arabica because the rules of the game are made for Arabica.

Constantin Hoppenz

We often view high-quality coffee only in terms of its potential. What can this coffee offer under the best possible conditions? That's unrealistic.

The conditions for a good cup of coffee are rarely met optimally. If the question of which coffee is good and which is less good is based on how many satisfying cups of coffee it ultimately produces, the average rather than the extreme is more important.

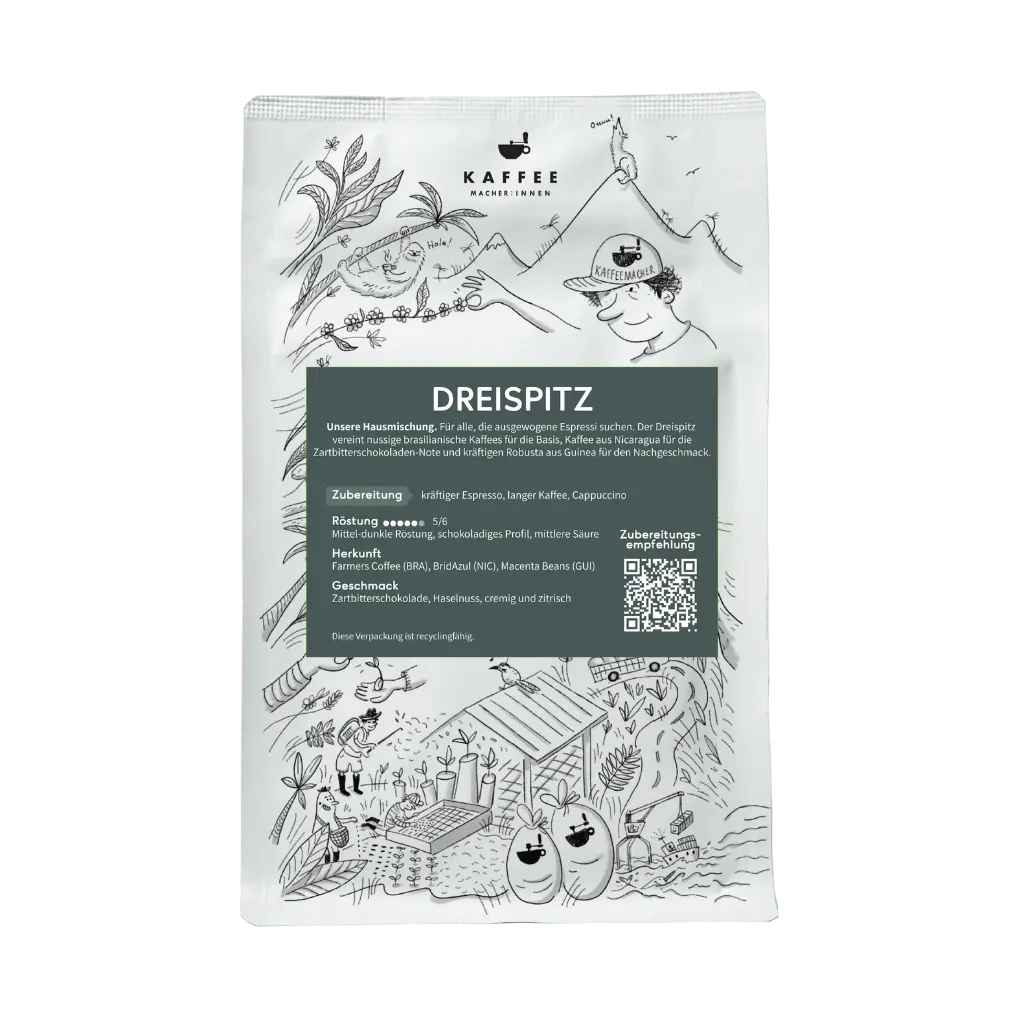

Robusta is much more palatable for espresso than Arabica. Coffee is generally under-extracted in most cafes, which makes a high-acid Arabica far less enjoyable than a Robusta.

In addition, a large portion is still prepared as a milk beverage. With its rich caramel flavors and body, Robusta appeals to most coffee drinkers. Mario Fernandez, Technical Director of ICO, described the difference between the two varieties in a very amusing but apt way:

If both were animals, Arabica would be the horse and Robusta the donkey. Robusta is a true workhorse, while Arabica is more of a show animal. Showing a donkey in dressage is as inappropriate as letting a horse climb steep mountain slopes as a pack animal.

Specialty Coffee is more than just taste

For most coffee enthusiasts, it all began with that first special cup of coffee. This experience with the first fruity natural coffee from Ethiopia remains etched in many minds. But specialty coffee is much more than what's in the cup. Specialty coffee represents a shift in thinking. It represents respect for products that have become far too commonplace. Good coffee also means good business practices.

Standards such as traceability and transparency, fair prices, and appreciation for hard work are expressions of values that make the world of specialty coffee unique. For me, they are the reason I work in this industry.

Constantin Hoppenz

If you represent these values with conviction, it is only logical to make the same claim for Robusta.

A roaster that claims to be a "specialty" coffee and stands for sustainability can't simultaneously rail against Robusta. Or is it perhaps unthinkable that a Robusta producer would want to produce the best possible quality, practice sustainable cultivation, and work directly with roasters?

It's not a compromise on quality if we, as the coffee industry, pay more attention to Robusta production. After all, the pursuit of ever-better coffee in the simplest sense eventually reaches its limits. Let's think about coffee in context. If we develop quality across the board instead of always pushing it upwards, we can ultimately inspire more people to enjoy coffee – whether Arabica or Robusta.

Constantin Hoppenz

Berlin, September 2019

How to taste Robusta properly? A report on the R-Grader course

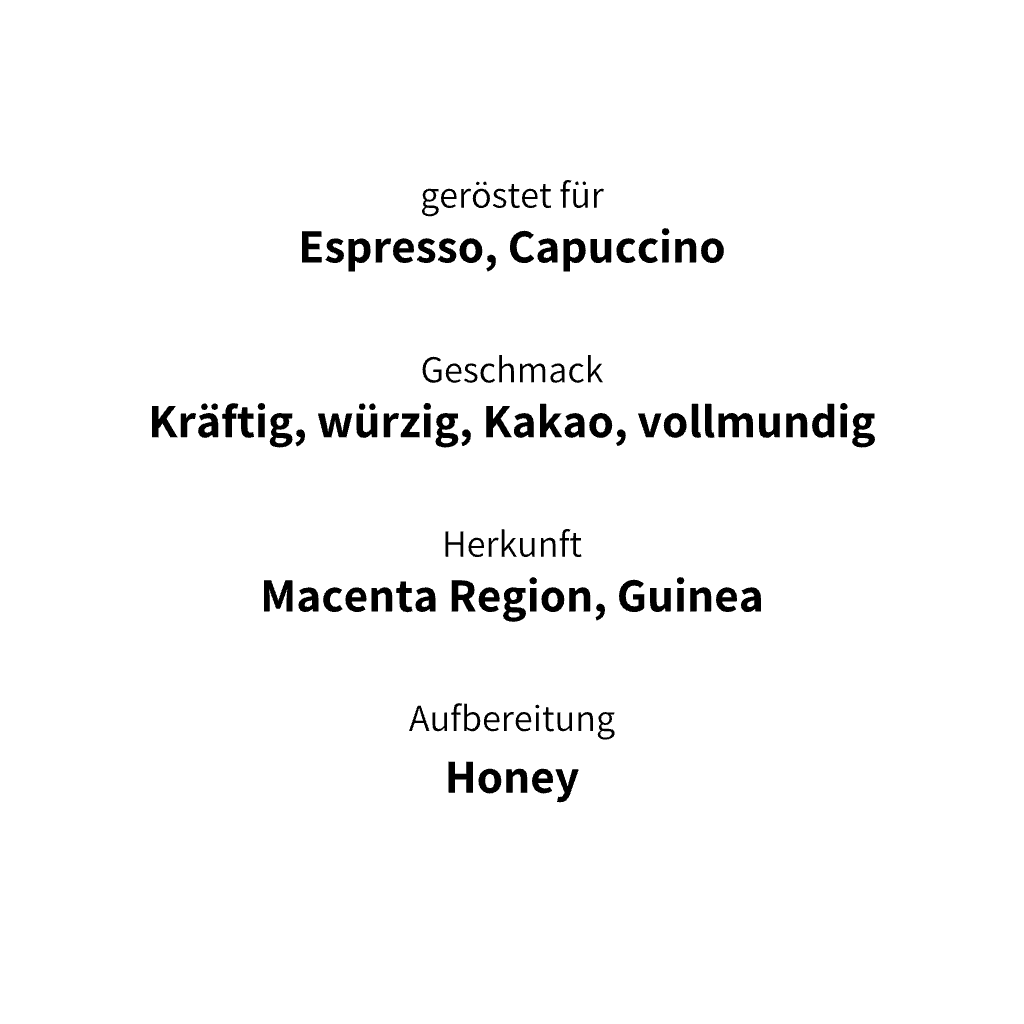

What does fine Robusta taste like as an espresso? Try our Robusta espresso from Java.