There are few companies as close to coffee as Cafeología. Located in southern Mexico, they work directly with producers, roast, taste, are baristas, and share their knowledge in their coffee school. The team led by Jesús Salazar has created a coffee island that could be groundbreaking for the entire coffee industry. Detail, precision, and patience characterize Cafeología's work. We were there.

"Caffeology" doesn't exist as a separate field, yet it's quickly clear what it's meant to be about: the entirety of what defines coffee. It's a holistic approach to a topic that encompasses production, processing, and consumption. " Caféología " is dedicated to this great goal as a company, stating that "harmony between the environment, families, and quality is paramount."

Cafeología's motto: We create the human, economic and material conditions to reflect the maximum expression of coffee and those who made it

What exactly does Cafeología do?

Many people who come into contact with Cafeología do so through social media. The company's Instagram accounts and those of Jesús (Cafeólogo) are a stylish diary of their work. The first physical point of contact is probably the cafes , with the headquarters in San Cristóbal being particularly noteworthy, as well as a small shop at Tuxtla Airport. At the headquarters in San Cristóbal, they operate a coffee roastery and a coffee school , where they train employees, coffee professionals, and interested parties.

They have a drying facility for coffee cherries on their roof. Outside the city, they operate a dry mill where they hull, sort, clean, and manually remove defects from coffee beans, and export green coffee, primarily to Europe. In the region around San Cristóbal, they work in four indigenous communities, where they run their own beneficios and offer quality optimization workshops to producers. This broad and diverse work has developed over the past ten years.

View into the Dry Mill, where coffees are sorted manually

In the fall of 2022, I was on-site in San Cristóbal, after we had already been in contact with Jesús for three years and had twice purchased a Natural Nano lot from Pedro Vásquez. I was both excited and nervous. Cafeología's medial work is impressive and creates high expectations.

The Cafeología Café

At the café, I met Pablo Salazar, who heads the finance department. The café itself is a mix of 70s architecture with lots of wood, high ceilings, plenty of plants, and subtle colors. The place itself exudes tranquility and invites you to enjoy several cups of coffee. The baristas are well-trained and take their time with the extractions.

Cafeología's flagship café in San Cristóbal

Guests can choose between coffees with different scores for their filter coffees. The 85-point coffees are the starting point, followed by the 86 and 87 points. The 85 points offer plenty of balance, a soft texture, and plenty of sweetness. The higher points become more floral and fruity, becoming less reminiscent of the classic coffee flavor.

“It’s all about the details,” says Pablo.

He's the company's CFO and only discovered coffee a few years ago when his brother Jesús recruited him for the project. "If we want to communicate details in coffee, we have to look at it in detail." Details—a word that would accompany me during my days in San Cristóbal.

Pablo Salazar, Cafeology

There were the specially designed coffee cups that concentrate the aroma and thus make it stronger. There was the soap made from coffee by-products in the room, there was the calibration in the language of all employees as they described the coffees. There was the same music in all rooms, there were the labeled cupping cups in the lab, and there was the same high quality coffee, no matter who brewed it.

The roastery

Right next to the café, Claudia and her team run the roastery . They roast on a 15kg Giesen roaster. They roast one curve for each type of coffee. The filter coffee roasting curve is their starting point; for espresso, they follow the same curve, but roast for a little longer. They now roast almost 30 tons for their own use. They serve five Cafeología cafés, sell on-site and through their online shop, and serve their coffee directly to several coffee shops in Mexico.

View into the roastery of Cafeología.

Awareness and consumption of local coffee are significantly higher in Mexico than in other coffee-producing countries. At Buna in Mexico City, for example, guests choose between different coffee regions, then the farm. It's essentially the same as we know from wine.

The coffee school and the laboratory

Claudia also runs the lab next door, where daily tastings take place. Claudia also judges the Cup of Excellence, the most prestigious competition for a country's best coffee. The tastings with Claudia and the team were very valuable, as they allowed us to calibrate ourselves.

We wanted to learn from each other how we think, talk, and feel about coffee. This will help us all communicate more accurately in the future, and Cafeología will find the coffees we're looking for.

The Cupping Lab of Cafeología

We tasted coffees from three regions around San Cristóbal. Cafeología focuses on washed, cherry-fermented, and dry-processed coffees. Carlos is responsible for the post-harvest processes, and I had a long conversation with him about fermentation and drying.

Carlos is responsible for the entire post-harvest process

However, Carlos wasn't talking about drying, but rather "dehydration"—that is, removing water. It seems like a detail, but that's exactly what it's all about. The way, speed, temperature, and sunlight we extract water from coffee have a massive impact on its flavor and shelf life.

Drying on the roof

The first drying beds were already standing right in front of my room. Where in other houses you'd find a balcony, where you'd sunbathe and drink a glass of wine, Carlos and his team were drying coffee cherries. A dream for any coffee lover.

Drone view of the roof of Cafeología shortly before the drying beds were carried up.

"Here we have total control over the process," he says, because he can check the progress of the drying and fermentation several times a day. While these are laboratory conditions, they can derive general recommendations that Diana and her agronomy team can then pass on to producers.

The focus on quality

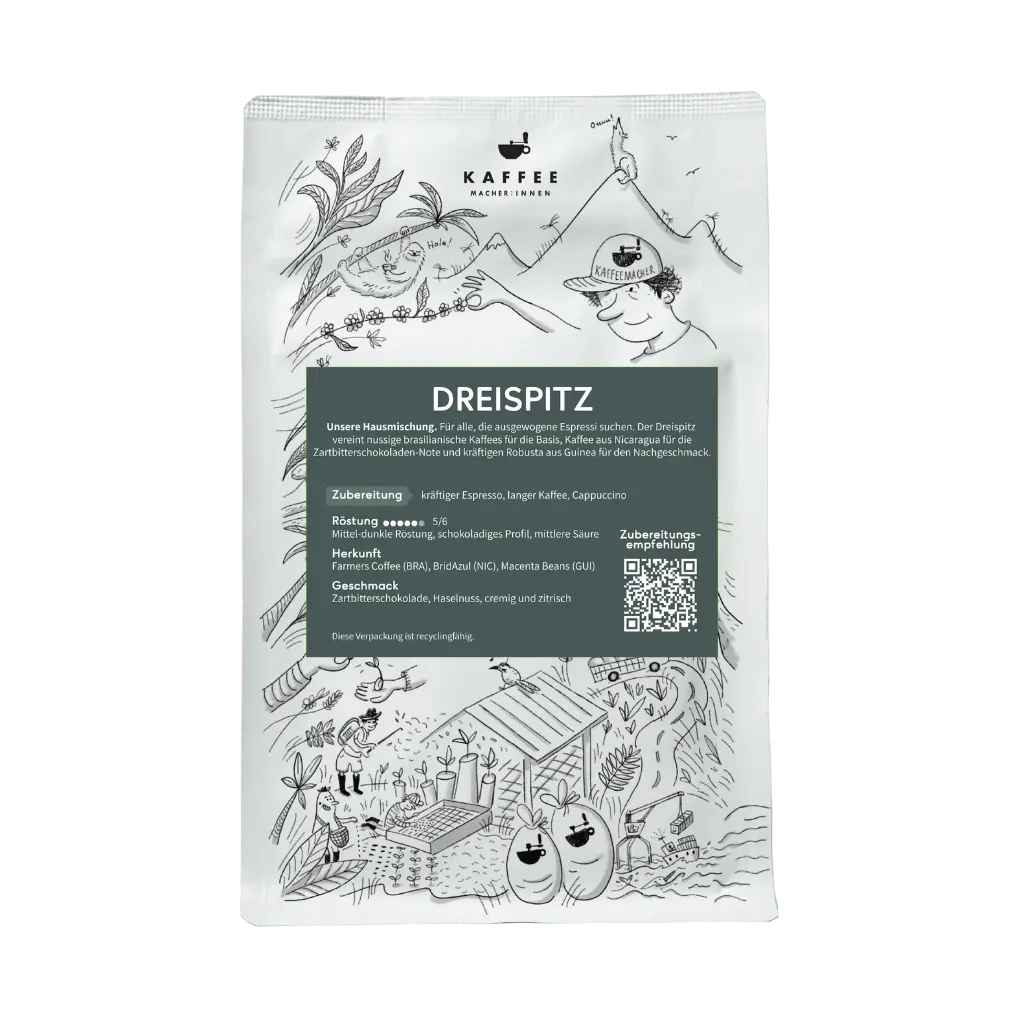

Cafeología will process approximately 70 tons of green coffee in 2022. That's roughly the same amount as we roasted in 2022. Of these 70 tons, they roast about half themselves, while the rest goes to the local specialty market or for export.

Cafeología focuses on distinctive, high-quality coffees with scores above 85 points according to the SCA standard. Not all coffees from the producers they work with directly reach 85 points. For those coffees that score between 84 and 85 points, they have created two dedicated cafés, the " Carajillo ." There, they offer specialty coffee that is somewhat more accessible, allowing them to create a larger market for their partner producers. They sell coffees below 84 points on the local green coffee market.

All producers receive this receipt, which certifies the quality of the cherries and defines the expected yield.

The strong focus on complex coffees is certainly interesting from a sensory perspective. However, it's worth considering whether this very focus also excludes producers, and if so, how.

Visit to Aldama at the Beneficio Comunitario

We visit the Beneficio Comunitario, a coffee cherry collection station. Cafeología built this station together with a local coffee producer. For this, we travel to Aldama, an indigenous Tzotzíl community not far from San Cristóbal. The two places are physically separated by a two-hour drive or 30 kilometers by air – but in terms of content, they're a universe apart.

"I grew up in Chiapas," says Pablo, "and never had to define myself by the color of my skin. I'm from here, after all. But when I was in Aldama for the first time, I was suddenly the white one."

Aldama lies east of San Cristóbal in a region that, in the 1990s, attracted considerable sympathy from the social-revolutionary Zapatista movement. The region's history is different from that of San Cristóbal. The rural areas are still strongly influenced by indigenous customs, traditions, and values. In the small communities, few people speak Spanish; the communities often remain and live among themselves. This fragmentation creates micro-regions and micro-worlds, so that Cafeología initially worked with three translators in the San Cristóbal area alone.

In Aldama itself, we meet Inéz Vázquez. She is the daughter of Pedro Vázquez, from whom we've already roasted two nano-lots. Inéz is a young woman who worked as a barista at Cafeología for five years, then roasted coffee, and now runs a coffee cherry collection center. This fact alone breaks with many traditions in her community: as a young woman, she takes on a job previously performed only by men. She manages the beneficio and thus not only has responsibility but is also endowed with many rights—she decides which quality cherries are purchased or rejected. At the same time, she provides feedback and conducts workshops for producers to convey Cafeología's philosophy.

Inéz Vázquez. Producer's daughter, entrepreneur, barista, roaster.

"The beginning was a bit bumpy," says Inéz. After three years, however, the number of producers supplying cherries to Inéz has tripled. The quality is constantly improving, and this is largely due to the simple, direct, and transparent way Cafeología and Inéz communicate their knowledge.

There are no surprises for producers because, firstly, Cafeología communicates the prices for delivered coffee cherries before the season and makes them public. What may sound somewhat obvious is precisely not standard practice in coffee-producing countries. Coffee is often harvested without knowing what the value will be at the end of the day. This seemingly small lever turns an entire system upside down.

Above all, it creates incentives in a region largely ignored by official Mexico. The recent history of the Zapatista region appears to be one reason why there are few government interventions or development programs to support the poor, rural population. Far too often, and in this case as well, there are government pensions that are supposed to support people, but in reality keep them silent and in a vicious cycle.

In the case of the region around Aldama, young people are entitled to their own home at the age of 15. There are no building zones. So anyone who wants to build can do so without major restrictions, no matter where. There's a government subsidy for this. Parents also receive a state pension for each child. And this combination creates the cocktail of many young people in the region who have many children and live in their own one-bedroom house. The money from the child pension is often enough to survive, but not much more.

Coffee quality as an incentive

"This isn't a system, it's stagnation," says Inéz. No incentives are created to do anything. Cafeología's system, however, is all about incentives. Aldama lies in a region between 1,800 and 2,000 meters above sea level. There's little coffee roasting in the region because it's very cool. Many producers work organically because they have no access to mineral fertilizers. Varieties like Gesha, Bourbon, and Java grow here, which are no longer cultivated in many parts of Mexico because they aren't Roya-resistant. The starting point for high quality is there. But to truly achieve this, plants need to be cared for and harvested precisely.

Claudia and Diana

Diana is an agronomist and supervises all the producers Cafeología works with. I love and appreciate working with agronomists, asking detailed questions, and receiving in-depth answers. Diana advises producers on how to make their farms sustainable for the long term, on suitable varieties for new plantings, on how to prevent diseases and pests, and on how to plant other crops between the coffee trees.

What about organic production? "Step by step," says Diana. Mexico and organic coffee is a story of its own. Since the 1980s, Mexico has been one of the largest producers of organic coffee, which is primarily exported to the USA. All of Mexico's coffee regions have embraced organic coffee, but their primary focus has been on certification rather than plant care.

"Many organic farms here are ruined," I heard again and again. Organic doesn't just happen. Organic isn't simply organic because nothing is done anymore. And this approach prevailed in Chiapas for a long time. "If you don't fertilize, if you don't prune, if you simply do nothing, you're organic," says Diana. But organic isn't about "doing nothing"—it's about working with the soil, the entire farm system, and that requires a deep understanding and a lot of work if it's to be successful.

"We must first demonstrate that we are trustworthy partners. Then we must demonstrate that we require high quality. And then we will slowly introduce our producers to natural production."

Many organic farms in the region think that organic = doing nothing

It's important to note that the vast majority of producers already work extremely close to nature with Cafeología, some even organically. However, there are also many negative and recent memories of organic certification.

Certification for individual producers is unrealistic, especially for small producers. One path to certification is offered by cooperatives, which in Mexico are often dual-certified as organic and Fairtrade. However, a cooperative alone doesn't make a difference; it must be conscientiously managed and developed in the service of its members. Too often, cooperatives have collapsed due to embezzlement of funds and the failure of individual members' opinions to be heard, leading to a loss of trust and the dissolution of many cooperatives.

"Paso por paso. Rushing doesn't help. We need to create understanding, gain trust, and then move forward step by step. We're still guests here." Diana, who comes from Colombia, notices this three times over: as a woman, as a white person, and as a Colombian.

The Dry Mill and the Export

Once the coffee is dry, it's prepared for export in the company's own dry mill. It was the first time I didn't wear a face mask in a dry mill. There was hardly any dust. "We clean the hulling machines after each run," says Pablo. Afterward, the green coffee is sorted by density and size. They repeat this process five times as standard—I've never seen that before.

The resulting high level of uniformity results in an extremely homogeneous roast quality, as all beans can process the roaster's energy evenly. This year, we purchased two Nanolots from Cafeología. The coffees are shipped to Europe via Belco.

We're delighted to be partnering with Cafeología. It's a pleasure to be able to share such a broad and in-depth understanding of coffee. We offer you annual nano-lots from the San Cristóbal region, and together we can get to know the region better, both sensorially and in depth.