The acidity in coffee is always a source of debate. Some love it, others prefer to avoid it. However, acidity is an essential component of every coffee and is responsible for the balance of flavor. We explain why acidity is so important and define what good and bad acids in coffee are.

I often hear the term "hipster coffee" when people talk about cafes that serve coffees that don't conform to the established norm. The criticism often begins with the claim that these coffees are "just sour" and have nothing to do with coffee.

As a coffee roaster and coffee school, we experience the same phenomenon again and again when people talk about a "really good espresso." This is often accompanied by the idea of a classic southern Italian espresso all'Italiana.

Of course, coffees with more acidity aren't a trend—and if they were, it would be one that's here to stay. We see this more as a development that allows us as consumers to become increasingly familiar with coffee.

For example, when our partners from Nicaragua come to us and taste an espresso, they can hardly finish the coffee.

Espresso in Europe is "too strong, too bitter, too intense." "And it lacks acidity!"

Team Santa Rita

Acidity in coffee: is it all a matter of perspective?

Most people discover coffee for the first time while traveling. Whether in cities with a high concentration of specialty cafés or in coffee-producing countries themselves, the coffee there usually tastes different from what we drink in Central Europe . Especially in coffee-producing countries, filtered or boiled coffee is consumed a lot; espresso is much less common.

In Central Europe, espresso made from darker roasted beans is still what many consider a good espresso. "A proper espresso" often means that the beans are also really dark.

When I first went to a specialty coffee shop in the US in 2009, I had a terrible espresso. It was just sour—and even though I was totally into acid at the time, I could barely drink it. The double ristretto was overdosed and under-extracted, and that too with a light roast. I didn't find it tasty, and I wouldn't find it tasty today either, but the coffee shop was doing well, and the customers liked the coffee.

Taste is learned. What we find tasty and what we don't is determined by our socialization, by our exposure to many or few foods. Whether we like coffees with little or a lot of acidity depends primarily on what we already know and, secondly, on how open we are to what doesn't correspond to our experience. Only then does our qualification begin, whether we like the coffee or not.

Acid in coffee divides minds and palates

When I drank my first acidic espresso from a well-known English roaster, I found it strange at first. If I believed the packaging, I was supposed to taste many more flavors. I literally had the feeling I wanted to like the coffee—and so I started looking for acidic coffees. But when I then drank a more normal coffee with barely perceptible acidity, something was missing. The coffee was dull, monotonous, and nothing happened. My tongue wasn't triggered.

At the same time, I realized that acidity is only one part of the whole taste experience. It's about balance. It's about sweetness. It's about complexity, the clarity of flavors, the intensity of attributes, and the pleasant texture.

Anyone interested in specialty coffee has probably already tasted coffees with more acidity than usual. Some stick with it, others go back. Some go back and realize what they've learned. Others go back and find very little to like about this type of coffee—which brings us back to perspectives.

The acid debate divides opinions and palates, and goes in circles. Therefore, in the following points, we explain what acid in coffee is, what it does, what it can do, and where it comes from.

Sour or acid? The pH value of coffee

Regardless of the topic, we can only describe things as precisely as we can express them. Sometimes language presents us with particular challenges. In Swiss German, the noun acid (Süüri) is used significantly less than the appellation "sour" (suur). Many things are simply "sour." "Suur" is also often used as an appellation for bad coffee.

Temperature and pH are measured here during the fermentation of coffee cherries.

In standard German, the situation is quite similar, except that—at least in product descriptions— acid is used more often than sour . Whether this is linguistic or not—technically speaking, they are different things.

And as is often the case, the English is even more precise here: Acidity in coffee is a positive description. But if a coffee is sour , it's a negative description.

Acids, on the other hand, are the acids, of which up to 40 can be measurably detected in a coffee.

Why is the acid-sour distinction so important?

Because technically they are two different things.

Acidity refers to the taste profile of the coffee.

Sour refers to the pH value of the coffee.

With a pH of approximately 5 (4.85–5.1 pH), coffee is a mildly acidic beverage. Tomato juice (pH 4) and soda (pH 3) are significantly more acidic. This is because the pH scale is logarithmic—a pH difference of 1 is 10x higher/lower. So, soda is 100 times more acidic than coffee.

Although it's easy to assume, the amount of acidity perceptible in the taste has no influence on the pH of the drink. In this case, a highly acidic espresso from Kenya has the same pH as a dark roast Malabar.

The difference between these coffees lies in the sensation of acidity, but they are both acidic.

Which acids do we taste in coffee?

Of the nearly 40 acids found in green coffee, chlorogenic acids account for the largest proportion. They occur at between 6-7% in Arabica and just under 10% in Robusta. Compared to caffeine (1-2%), the chlorogenic acid content in coffee is significantly higher.

Chlorogenic acids are a family of diverse, naturally occurring compounds—some that degrade during roasting (mono-caffeeoyl) and some that barely change during roasting (di-caffeeoyl). Chlorogenic acids break down during roasting into the bitter-tasting chlorogenic acid lactones. And because Robusta has more chlorogenic acids than Arabica, the latter is already more bitter. Coffeeness has covered chlorogenic acids in detail here .

Many of the acids present in green coffee don't survive the roasting process. The longer and darker the roasting, the more the perceptible acids break down.

In terms of taste, however, we can only distinguish a few acids from all those present.

citric acid

The most concentrated acid in coffee. It's the acid present in every coffee—and, depending on its intensity, can be more or less easily identified as such. Citrus acid occurs naturally in the plant's metabolism and plays an important role as an energy source. Its flavor is reminiscent of—how could it be otherwise—citrus fruits (lemons, limes, oranges).

Malic acid

Malic acid is found in apples, pears, and even rhubarb. In wine production, it is replaced by lactic acid during malolactic fermentation because it can have aggressive, acidic properties. In coffee, it often occurs in a similar way to citrus acid, but is somewhat smoother, more balanced, and for many, in a different place on the tongue.

Phosphoric acid

Phosphoric acid is not an organic acid, but a mineral acid. It is supposedly absorbed through the composition of the soil and/or the type of fertilization the plant receives. The acid is often somewhat bitter, sometimes tingling, and harsh. We often find it in Kenyan coffees.

Acetic acid

Acetic acid can be extremely unpleasant in high concentrations. It occurs when the coffee has a defect resulting from uncontrolled fermentation. New types of post-processing and fermentation in coffee also introduce more acetic acid into the flavor. When this process is controlled, a certain degree of acetic acid creates a fruity effect and contributes to a positive overall impression.

Lactic acid

The lactic acid in coffee has a similar quality to the acidity of quark—slightly tart, rather sour, but heavy. Through targeted fermentation of the coffee during the post-harvest process, the lactic acid content can be increased, which influences the softness of the texture.

3 takeaways at this point:

- One of the most exciting aspects of acids in coffee is the combination of different acids —and simultaneously in the same coffee. When several different acids are present simultaneously, the flavor impression is significantly stronger. We then speak of complex acids.

- A coffee is sour when it isn't supported by sweetness. In that case, we're talking about lower-quality coffee.

- A coffee without acid results in a very flat coffee. Or you might ask yourself: what would a white wine taste like without acid? Just flat.

Does acid upset your stomach?

The topic of health and coffee would deserve a whole post of its own—if the evidence against coffee were truly overwhelming. Coffee is attributed about as many negative effects as positive ones. It seems like the topic is brought to the surface during the summer lull and then fades away for another year. One thing is certain: everyone reacts differently to coffee. Arne Preuss has beautifully covered this debate in a blog post.

Where does the acid in coffee come from?

During the processing steps from the coffee tree to the cup, there are various stages where the coffee can retain or lose its acidity. It all starts with the plant.

Plant / cultivation

Cellular respiration is responsible for plant growth and the development of cherries. This process produces various acids. The formation of these acids is influenced by the growing conditions.

One factor in particular plays a major role here: temperature. At higher altitudes, or further from the equator , and/or in shady locations, temperatures are lower. This slows the growth of coffee plants and their cherries. With a slower growth rate, the plant focuses more on reproduction and therefore invests more in the development of healthy seeds. Slower-growing coffee seeds contain more proteins, sugars, fats, and acids than faster-growing ones. Conversely, the caffeine content is lower in slow-growing coffee.

Species and varieties

The acidity is higher in Arabicas than in Canephoras (Robustas). There are also differences within the varieties, especially among Arabicas, but they are very small. Parainemas, for example, a hybrid from Honduras, exhibits significantly more citrus notes under the same growing conditions than IHCAFE90, another hybrid. I once had the opportunity to taste a test series of different varieties grown under the same conditions at an exporter. The Parainema stood out. However, the differences are otherwise much smaller and negligible here.

Post-harvest processes

In our extensive article on post-harvest processes and fermentation, we delve into exactly what happens after the coffee cherry is picked. In short: pulped, fermented, and washed coffees have the potential to exhibit more perceptible acidity than coffees dried within the cherry—if the cherry is sent directly to drying. The storage of the cherry (barrel, barrel, tank, bag, etc.) can primarily influence the acetic acid level. However, post-harvest processes do not regulate the acids, but rather add new flavors or can mask existing ones.

How the coffee cherries are processed after picking has a major influence on the taste.

Roast

Longer roasting times and higher final temperatures minimize organic acids. However, acetic acid reaches a brief, unstable peak when coffee is roasted into the second crack. All other organic acids degrade over the duration and increasing temperature of the roast.

The yellow curve accentuates the acids, the red curve leads to a balanced coffee, while the blue curve reduces many acids.

preparation

While the type of acid is determined by the factors already discussed, the brewing method is responsible for the amount of extracted acid. Grind size, brewing temperature, brewing time, pressure, and turbulence during brewing all influence the total acidity that can end up in the cup if it isn't buffered by the water.

Water

Water with high alkalinity buffers, or neutralizes, the perceptible acids in coffee. At the same time, it also pulls the pH toward alkaline. Thus, water manages to simultaneously alter acid and acidity, making it the invisible yet powerful component. We've described which water is best for which beverage in this detailed article.

Perceived acidity in espresso, filter coffee, and fully automatic coffee

When we talk about "acidic coffee," what kind of beverage are we talking about exactly? This aspect, too, is strongly linked to our experience of and expectations of coffee. Personally, I almost exclusively think of filter coffee when I think of coffee.

Many people find it easier to accept acidity in filter coffee. This is primarily due to the fact that the coffee concentration in filter coffee is significantly lower (approximately 1.5% of the drink is coffee, the rest is water) than in espresso (approximately 10% of the drink is coffee). Espresso is an incredibly intense, concentrated drink. If a coffee has little acidity in a filter coffee, it will have much more acidity in an espresso.

In our roastery, we only use acidic coffees for espresso if we also detect a high level of sweetness—this pairing then creates a flavor balance. Without this balance, the coffee would be primarily acidic and difficult to enjoy. But even with balanced coffees that are acidic and even lighter roasted, the perceived acidity remains.

And not everyone likes that, and it doesn’t have to.

However, the perceived acidity of filter coffee plays a less dramatic role for many. Since filter coffee is a diluted coffee beverage, a perceptible acidity is beneficial, giving the coffee structure and tension. Without acidity, filter coffee would be very flat.

The situation is different again with fully automatic coffee machines. Those who work with acidic coffees will have less enjoyment from their espressos.

Why?

In fully automatic coffee machines, which typically brew at temperatures below 90°C in household use, acidic coffees taste even more acidic. The brewing temperature is low, and the grind is relatively coarse, so less sweetness and fewer texture-forming starch particles can be extracted.

Light roasted coffees, for example, tend to taste exclusively sour on a standard fully automatic coffee machine. That's why we roast differently for fully automatic coffee machines and offer training in this area during our consultations.

Good acids, bad acids

Good acids give the coffee freshness, complexity, excitement and often make us think of specific fruits.

Bad acids have an aggressive, drying effect and can be sharp and pungent. This is often the case when there is little to no sweetness in the coffee.

"Sweetness supports acidity," a former fellow judge once told me. When there's a lot of sweetness, acidity becomes more exciting. The opposite is also true.

The challenge of communicating acid positively

We coffee makers like coffees that exhibit a distinct acidity. Therefore, we work with green coffees that already possess this acidity and roast the coffees mostly to a light to medium-light roast. This type of roast retains many of the acidity in the coffee.

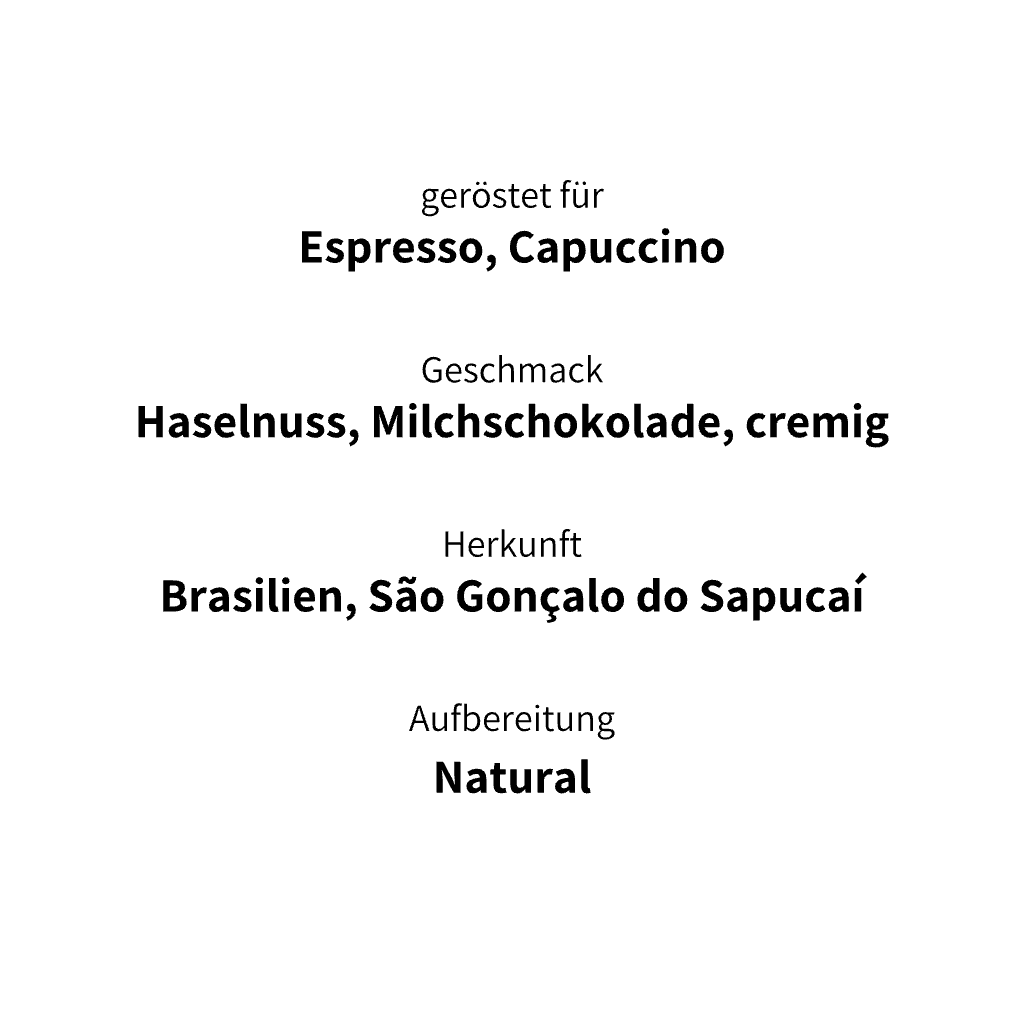

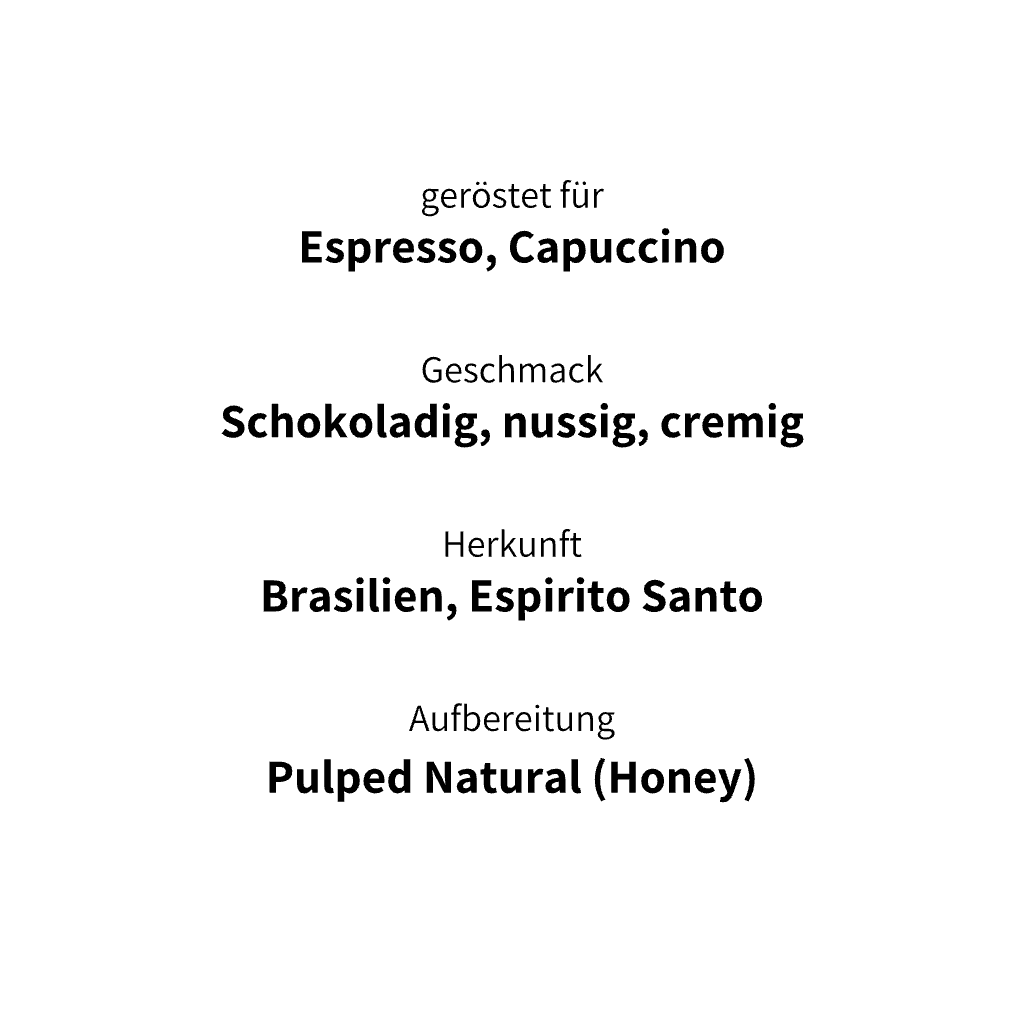

Of course, we also all like coffees that are sometimes milder, sometimes a bit more chocolatey, and lower in acidity. For example, our APAS or the Henrique from Brazil—both coffees that, by our definition, have less acidity.

For our courses, we use coffee from the APAS cooperative, as it has a more classic, nutty-chocolaty profile with less acidity. This profile is familiar to most course participants and poses significantly less of a challenge than if we were working with a light-roasted specialty espresso.

As has already become clear, it's not easy to communicate acidity in a positive way – because there's often a negative attitude towards it. We don't see it as our job to fight it frantically; that's not productive. And above all, we are staunch opponents of a dictatorship of taste. Tastes are individual and change only slowly.

We see this as a different way to make specialty coffee – with little or a lot of acidity – tasty.

1. Less focus on acid in communication

At the beginning, I wrote that discussions about acidity in coffee tend to go around in circles. Perhaps this is because sometimes there's a bit too much focus on this topic?

In conversations, it often sounds as if good coffee exists only between the opposing forces of acidity and bitterness. However, anyone who has delved deeper into the subject knows that there are worlds of flavor, complexity, and balance in between.

Perhaps it would be more appropriate to move away from the acid-bitter duality and describe coffee differently?

So why not focus on body and texture? This coffee attribute is so special because it's the only one that isn't learned; we feel it, not taste it. Whether a coffee is creamy or watery is something everyone can feel, without prior knowledge. But whether a coffee has citrus or malic acidity is a much more complex matter that requires training.

2. Describe acid differently

When I participated in the Swiss Barista Championship in 2010, I would have described the coffee as "as if it only tasted like acidic toilet cleaner." That's what a somewhat challenged spectator said after my presentation.

I, new to the business at the time, was initially defensive because I liked my coffee. But when I looked at my descriptions again, they were all quite similar. They talked about citrus notes, tangy, "citric," clementines, and citrus acidity.

If I were to describe the same coffee again today, I would do it significantly differently. I now know that acidity is only part of the whole, that texture is my priority, and that similar descriptions aren't as precise.

We describe coffees differently today, too – one simple lever is that we associate more acidic coffees with fruit. In El Colibri, a Peruvian coffee that we roast as an espresso, we find tartaric acidity.

If we were to describe coffee to a wider audience as containing "tartaric acid," it would confuse rather than help. The association with wine is there, and very few people have ever tasted tartaric acid on its own.

So it makes sense to switch to grapes that are full of tartaric acid. Coffee generally has lighter flavors, so we opted for raisin and "white wine-like" coffee.

3. Accept that acid is simply not for everyone

Sounds logical? Maybe, but it's still not easy.

Many people appreciate specialty coffee for its variety of flavors, its uniqueness, its new sensory experiences, and perhaps the stories behind the coffees.

When I first made a specialty espresso for a friend in 2009, the coffee was indeed very acidic. Perhaps it was even very sour, but back then I was looking for something different. The friend in question pulled a face and looked at me in confusion, but tried hard to detect anything besides the aggressive acidity.

He didn't like any of the coffees that evening. I don't remember if I liked them either. But I tried.

So the acidity immediately became the focus of the discussion—not the variety, not the roasting method, not the origin, not the fancy branding. I tried to explain to him why it contained acidity, why it was less intense in other coffees, and why it was a positive thing.

I could never convince him. At first, I even thought I had to. Today, he drinks our Henrique and is incredibly satisfied. A medium-dark roast with less acidity. Totally his thing.

Over the years, I've learned that acidity is often at the center of discussions about specialty coffee. So, it makes sense for us today to showcase more classic, nuttier coffees, or the complete opposite—extremely aromatic coffees, such as Naturals from Ethiopia. Coffees that smell so intensely different that we first talk about the aroma, make wine comparisons, recognize the complexity, and then, at some point, talk about the acidity.

Conclusion

Explaining to someone that acidity in coffee can be a positive thing is a difficult approach to explaining specialty coffee. These arguments, even if they are sound, rarely resonate with them. However, if the focus is on texture and aroma, the first hurdle is overcome.

The acidity in coffee is always a source of debate. Some love it, others prefer to avoid it. However, acidity is an essential component of every coffee and is responsible for the balance of flavor. We explain why acidity is so important and define what good and bad acids in coffee are.

I often hear the term "hipster coffee" when people talk about cafes that serve coffees that don't conform to the established norm. The criticism often begins with the claim that these coffees are "just sour" and have nothing to do with coffee.

As a coffee roaster and coffee school, we experience the same phenomenon again and again when people talk about a "really good espresso." This is often accompanied by the idea of a classic southern Italian espresso all'Italiana.

Of course, coffees with more acidity aren't a trend—and if they were, it would be one that's here to stay. We see this more as a development that allows us as consumers to become increasingly familiar with coffee.

For example, when our partners from Nicaragua come to us and taste an espresso, they can hardly finish the coffee.

Espresso in Europe is "too strong, too bitter, too intense." "And it lacks acidity!"

Team Santa Rita

Acidity in coffee: is it all a matter of perspective?

Most people discover coffee for the first time while traveling. Whether in cities with a high concentration of specialty cafés or in coffee-producing countries themselves, the coffee there usually tastes different from what we drink in Central Europe . Especially in coffee-producing countries, filtered or boiled coffee is consumed a lot; espresso is much less common.

In Central Europe, espresso made from darker roasted beans is still what many consider a good espresso. "A proper espresso" often means that the beans are also really dark.

When I first went to a specialty coffee shop in the US in 2009, I had a terrible espresso. It was just sour—and even though I was totally into acid at the time, I could barely drink it. The double ristretto was overdosed and under-extracted, and that too with a light roast. I didn't find it tasty, and I wouldn't find it tasty today either, but the coffee shop was doing well, and the customers liked the coffee.

Taste is learned. What we find tasty and what we don't is determined by our socialization, by our exposure to many or few foods. Whether we like coffees with little or a lot of acidity depends primarily on what we already know and, secondly, on how open we are to what doesn't correspond to our experience. Only then does our qualification begin, whether we like the coffee or not.

Acid in coffee divides minds and palates

When I drank my first acidic espresso from a well-known English roaster, I found it strange at first. If I believed the packaging, I was supposed to taste many more flavors. I literally had the feeling I wanted to like the coffee—and so I started looking for acidic coffees. But when I then drank a more normal coffee with barely perceptible acidity, something was missing. The coffee was dull, monotonous, and nothing happened. My tongue wasn't triggered.

At the same time, I realized that acidity is only one part of the whole taste experience. It's about balance. It's about sweetness. It's about complexity, the clarity of flavors, the intensity of attributes, and the pleasant texture.

Anyone interested in specialty coffee has probably already tasted coffees with more acidity than usual. Some stick with it, others go back. Some go back and realize what they've learned. Others go back and find very little to like about this type of coffee—which brings us back to perspectives.

The acid debate divides opinions and palates, and goes in circles. Therefore, in the following points, we explain what acid in coffee is, what it does, what it can do, and where it comes from.

Sour or acid? The pH value of coffee

Regardless of the topic, we can only describe things as precisely as we can express them. Sometimes language presents us with particular challenges. In Swiss German, the noun acid (Süüri) is used significantly less than the appellation "sour" (suur). Many things are simply "sour." "Suur" is also often used as an appellation for bad coffee.

Temperature and pH are measured here during the fermentation of coffee cherries.

In standard German, the situation is quite similar, except that—at least in product descriptions— acid is used more often than sour . Whether this is linguistic or not—technically speaking, they are different things.

And as is often the case, the English is even more precise here: Acidity in coffee is a positive description. But if a coffee is sour , it's a negative description.

Acids, on the other hand, are the acids, of which up to 40 can be measurably detected in a coffee.

Why is the acid-sour distinction so important?

Because technically they are two different things.

Acidity refers to the taste profile of the coffee.

Sour refers to the pH value of the coffee.

With a pH of approximately 5 (4.85–5.1 pH), coffee is a mildly acidic beverage. Tomato juice (pH 4) and soda (pH 3) are significantly more acidic. This is because the pH scale is logarithmic—a pH difference of 1 is 10x higher/lower. So, soda is 100 times more acidic than coffee.

Although it's easy to assume, the amount of acidity perceptible in the taste has no influence on the pH of the drink. In this case, a highly acidic espresso from Kenya has the same pH as a dark roast Malabar.

The difference between these coffees lies in the sensation of acidity, but they are both acidic.

Which acids do we taste in coffee?

Of the nearly 40 acids found in green coffee, chlorogenic acids account for the largest proportion. They occur at between 6-7% in Arabica and just under 10% in Robusta. Compared to caffeine (1-2%), the chlorogenic acid content in coffee is significantly higher.

Chlorogenic acids are a family of diverse, naturally occurring compounds—some that degrade during roasting (mono-caffeeoyl) and some that barely change during roasting (di-caffeeoyl). Chlorogenic acids break down during roasting into the bitter-tasting chlorogenic acid lactones. And because Robusta has more chlorogenic acids than Arabica, the latter is already more bitter. Coffeeness has covered chlorogenic acids in detail here .

Many of the acids present in green coffee don't survive the roasting process. The longer and darker the roasting, the more the perceptible acids break down.

In terms of taste, however, we can only distinguish a few acids from all those present.

citric acid

The most concentrated acid in coffee. It's the acid present in every coffee—and, depending on its intensity, can be more or less easily identified as such. Citrus acid occurs naturally in the plant's metabolism and plays an important role as an energy source. Its flavor is reminiscent of—how could it be otherwise—citrus fruits (lemons, limes, oranges).

Malic acid

Malic acid is found in apples, pears, and even rhubarb. In wine production, it is replaced by lactic acid during malolactic fermentation because it can have aggressive, acidic properties. In coffee, it often occurs in a similar way to citrus acid, but is somewhat smoother, more balanced, and for many, in a different place on the tongue.

Phosphoric acid

Phosphoric acid is not an organic acid, but a mineral acid. It is supposedly absorbed through the composition of the soil and/or the type of fertilization the plant receives. The acid is often somewhat bitter, sometimes tingling, and harsh. We often find it in Kenyan coffees.

Acetic acid

Acetic acid can be extremely unpleasant in high concentrations. It occurs when the coffee has a defect resulting from uncontrolled fermentation. New types of post-processing and fermentation in coffee also introduce more acetic acid into the flavor. When this process is controlled, a certain degree of acetic acid creates a fruity effect and contributes to a positive overall impression.

Lactic acid

The lactic acid in coffee has a similar quality to the acidity of quark—slightly tart, rather sour, but heavy. Through targeted fermentation of the coffee during the post-harvest process, the lactic acid content can be increased, which influences the softness of the texture.

3 takeaways at this point:

- One of the most exciting aspects of acids in coffee is the combination of different acids —and simultaneously in the same coffee. When several different acids are present simultaneously, the flavor impression is significantly stronger. We then speak of complex acids.

- A coffee is sour when it isn't supported by sweetness. In that case, we're talking about lower-quality coffee.

- A coffee without acid results in a very flat coffee. Or you might ask yourself: what would a white wine taste like without acid? Just flat.

Does acid upset your stomach?

The topic of health and coffee would deserve a whole post of its own—if the evidence against coffee were truly overwhelming. Coffee is attributed about as many negative effects as positive ones. It seems like the topic is brought to the surface during the summer lull and then fades away for another year. One thing is certain: everyone reacts differently to coffee. Arne Preuss has beautifully covered this debate in a blog post.

Where does the acid in coffee come from?

During the processing steps from the coffee tree to the cup, there are various stages where the coffee can retain or lose its acidity. It all starts with the plant.

Plant / cultivation

Cellular respiration is responsible for plant growth and the development of cherries. This process produces various acids. The formation of these acids is influenced by the growing conditions.

One factor in particular plays a major role here: temperature. At higher altitudes, or further from the equator , and/or in shady locations, temperatures are lower. This slows the growth of coffee plants and their cherries. With a slower growth rate, the plant focuses more on reproduction and therefore invests more in the development of healthy seeds. Slower-growing coffee seeds contain more proteins, sugars, fats, and acids than faster-growing ones. Conversely, the caffeine content is lower in slow-growing coffee.

Species and varieties

The acidity is higher in Arabicas than in Canephoras (Robustas). There are also differences within the varieties, especially among Arabicas, but they are very small. Parainemas, for example, a hybrid from Honduras, exhibits significantly more citrus notes under the same growing conditions than IHCAFE90, another hybrid. I once had the opportunity to taste a test series of different varieties grown under the same conditions at an exporter. The Parainema stood out. However, the differences are otherwise much smaller and negligible here.

Post-harvest processes

In our extensive article on post-harvest processes and fermentation, we delve into exactly what happens after the coffee cherry is picked. In short: pulped, fermented, and washed coffees have the potential to exhibit more perceptible acidity than coffees dried within the cherry—if the cherry is sent directly to drying. The storage of the cherry (barrel, barrel, tank, bag, etc.) can primarily influence the acetic acid level. However, post-harvest processes do not regulate the acids, but rather add new flavors or can mask existing ones.

How the coffee cherries are processed after picking has a major influence on the taste.

Roast

Longer roasting times and higher final temperatures minimize organic acids. However, acetic acid reaches a brief, unstable peak when coffee is roasted into the second crack. All other organic acids degrade over the duration and increasing temperature of the roast.

The yellow curve accentuates the acids, the red curve leads to a balanced coffee, while the blue curve reduces many acids.

preparation

While the type of acid is determined by the factors already discussed, the brewing method is responsible for the amount of extracted acid. Grind size, brewing temperature, brewing time, pressure, and turbulence during brewing all influence the total acidity that can end up in the cup if it isn't buffered by the water.

Water

Water with high alkalinity buffers, or neutralizes, the perceptible acids in coffee. At the same time, it also pulls the pH toward alkaline. Thus, water manages to simultaneously alter acid and acidity, making it the invisible yet powerful component. We've described which water is best for which beverage in this detailed article.

Perceived acidity in espresso, filter coffee, and fully automatic coffee

When we talk about "acidic coffee," what kind of beverage are we talking about exactly? This aspect, too, is strongly linked to our experience of and expectations of coffee. Personally, I almost exclusively think of filter coffee when I think of coffee.

Many people find it easier to accept acidity in filter coffee. This is primarily due to the fact that the coffee concentration in filter coffee is significantly lower (approximately 1.5% of the drink is coffee, the rest is water) than in espresso (approximately 10% of the drink is coffee). Espresso is an incredibly intense, concentrated drink. If a coffee has little acidity in a filter coffee, it will have much more acidity in an espresso.

In our roastery, we only use acidic coffees for espresso if we also detect a high level of sweetness—this pairing then creates a flavor balance. Without this balance, the coffee would be primarily acidic and difficult to enjoy. But even with balanced coffees that are acidic and even lighter roasted, the perceived acidity remains.

And not everyone likes that, and it doesn’t have to.

However, the perceived acidity of filter coffee plays a less dramatic role for many. Since filter coffee is a diluted coffee beverage, a perceptible acidity is beneficial, giving the coffee structure and tension. Without acidity, filter coffee would be very flat.

The situation is different again with fully automatic coffee machines. Those who work with acidic coffees will have less enjoyment from their espressos.

Why?

In fully automatic coffee machines, which typically brew at temperatures below 90°C in household use, acidic coffees taste even more acidic. The brewing temperature is low, and the grind is relatively coarse, so less sweetness and fewer texture-forming starch particles can be extracted.

Light roasted coffees, for example, tend to taste exclusively sour on a standard fully automatic coffee machine. That's why we roast differently for fully automatic coffee machines and offer training in this area during our consultations.

Good acids, bad acids

Good acids give the coffee freshness, complexity, excitement and often make us think of specific fruits.

Bad acids have an aggressive, drying effect and can be sharp and pungent. This is often the case when there is little to no sweetness in the coffee.

"Sweetness supports acidity," a former fellow judge once told me. When there's a lot of sweetness, acidity becomes more exciting. The opposite is also true.

The challenge of communicating acid positively

We coffee makers like coffees that exhibit a distinct acidity. Therefore, we work with green coffees that already possess this acidity and roast the coffees mostly to a light to medium-light roast. This type of roast retains many of the acidity in the coffee.

Of course, we also all like coffees that are sometimes milder, sometimes a bit more chocolatey, and lower in acidity. For example, our APAS or the Henrique from Brazil—both coffees that, by our definition, have less acidity.

For our courses, we use coffee from the APAS cooperative, as it has a more classic, nutty-chocolaty profile with less acidity. This profile is familiar to most course participants and poses significantly less of a challenge than if we were working with a light-roasted specialty espresso.

As has already become clear, it's not easy to communicate acidity in a positive way – because there's often a negative attitude towards it. We don't see it as our job to fight it frantically; that's not productive. And above all, we are staunch opponents of a dictatorship of taste. Tastes are individual and change only slowly.

We see this as a different way to make specialty coffee – with little or a lot of acidity – tasty.

1. Less focus on acid in communication

At the beginning, I wrote that discussions about acidity in coffee tend to go around in circles. Perhaps this is because sometimes there's a bit too much focus on this topic?

In conversations, it often sounds as if good coffee exists only between the opposing forces of acidity and bitterness. However, anyone who has delved deeper into the subject knows that there are worlds of flavor, complexity, and balance in between.

Perhaps it would be more appropriate to move away from the acid-bitter duality and describe coffee differently?

So why not focus on body and texture? This coffee attribute is so special because it's the only one that isn't learned; we feel it, not taste it. Whether a coffee is creamy or watery is something everyone can feel, without prior knowledge. But whether a coffee has citrus or malic acidity is a much more complex matter that requires training.

2. Describe acid differently

When I participated in the Swiss Barista Championship in 2010, I would have described the coffee as "as if it only tasted like acidic toilet cleaner." That's what a somewhat challenged spectator said after my presentation.

I, new to the business at the time, was initially defensive because I liked my coffee. But when I looked at my descriptions again, they were all quite similar. They talked about citrus notes, tangy, "citric," clementines, and citrus acidity.

If I were to describe the same coffee again today, I would do it significantly differently. I now know that acidity is only part of the whole, that texture is my priority, and that similar descriptions aren't as precise.

We describe coffees differently today, too – one simple lever is that we associate more acidic coffees with fruit. In El Colibri, a Peruvian coffee that we roast as an espresso, we find tartaric acidity.

If we were to describe coffee to a wider audience as containing "tartaric acid," it would confuse rather than help. The association with wine is there, and very few people have ever tasted tartaric acid on its own.

So it makes sense to switch to grapes that are full of tartaric acid. Coffee generally has lighter flavors, so we opted for raisin and "white wine-like" coffee.

3. Accept that acid is simply not for everyone

Sounds logical? Maybe, but it's still not easy.

Many people appreciate specialty coffee for its variety of flavors, its uniqueness, its new sensory experiences, and perhaps the stories behind the coffees.

When I first made a specialty espresso for a friend in 2009, the coffee was indeed very acidic. Perhaps it was even very sour, but back then I was looking for something different. The friend in question pulled a face and looked at me in confusion, but tried hard to detect anything besides the aggressive acidity.

He didn't like any of the coffees that evening. I don't remember if I liked them either. But I tried.

So the acidity immediately became the focus of the discussion—not the variety, not the roasting method, not the origin, not the fancy branding. I tried to explain to him why it contained acidity, why it was less intense in other coffees, and why it was a positive thing.

I could never convince him. At first, I even thought I had to. Today, he drinks our Henrique and is incredibly satisfied. A medium-dark roast with less acidity. Totally his thing.

Over the years, I've learned that acidity is often at the center of discussions about specialty coffee. So, it makes sense for us today to showcase more classic, nuttier coffees, or the complete opposite—extremely aromatic coffees, such as Naturals from Ethiopia. Coffees that smell so intensely different that we first talk about the aroma, make wine comparisons, recognize the complexity, and then, at some point, talk about the acidity.

Conclusion

Explaining to someone that acidity in coffee can be a positive thing is a difficult approach to explaining specialty coffee. These arguments, even if they are sound, rarely resonate with them. However, if the focus is on texture and aroma, the first hurdle is overcome.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.