Café crème is the most popular coffee beverage in Switzerland. It's all the more surprising how little discussion there is about this central beverage. Every barista whips out recipes for espresso and filter coffee without a second thought, but stutters when it comes to café crème. Since 2015, we have been advocating for a quality discussion on the topic of café crème. In this article, we collect recipes, document a consumer tasting we conducted with the Swiss Coffee Association Cafetiersuisse, and provide a brief history of café crème.

Café crème recipe

The best café crème can be brewed with an espresso machine using a dedicated grinder. Using a double portafilter, 12–15 grams of coffee are used. The grind is coarser than for an espresso. Brew in approximately 25–30 seconds at a ratio of 1:10. Using 12 grams, you'll brew 120 grams of café crème, while using 15 grams will produce up to 150 grams. The grind should be selected to create sufficient resistance so that the brewing water can't flow through the coffee puck faster than 25 seconds.

Please note: Some espresso machines have flow-limiting features, such as a flow meter. They can't deliver enough hot water quickly enough. With these espresso machines, preparing a Cafe Americano is a better option.

Consumer tasting Café crème

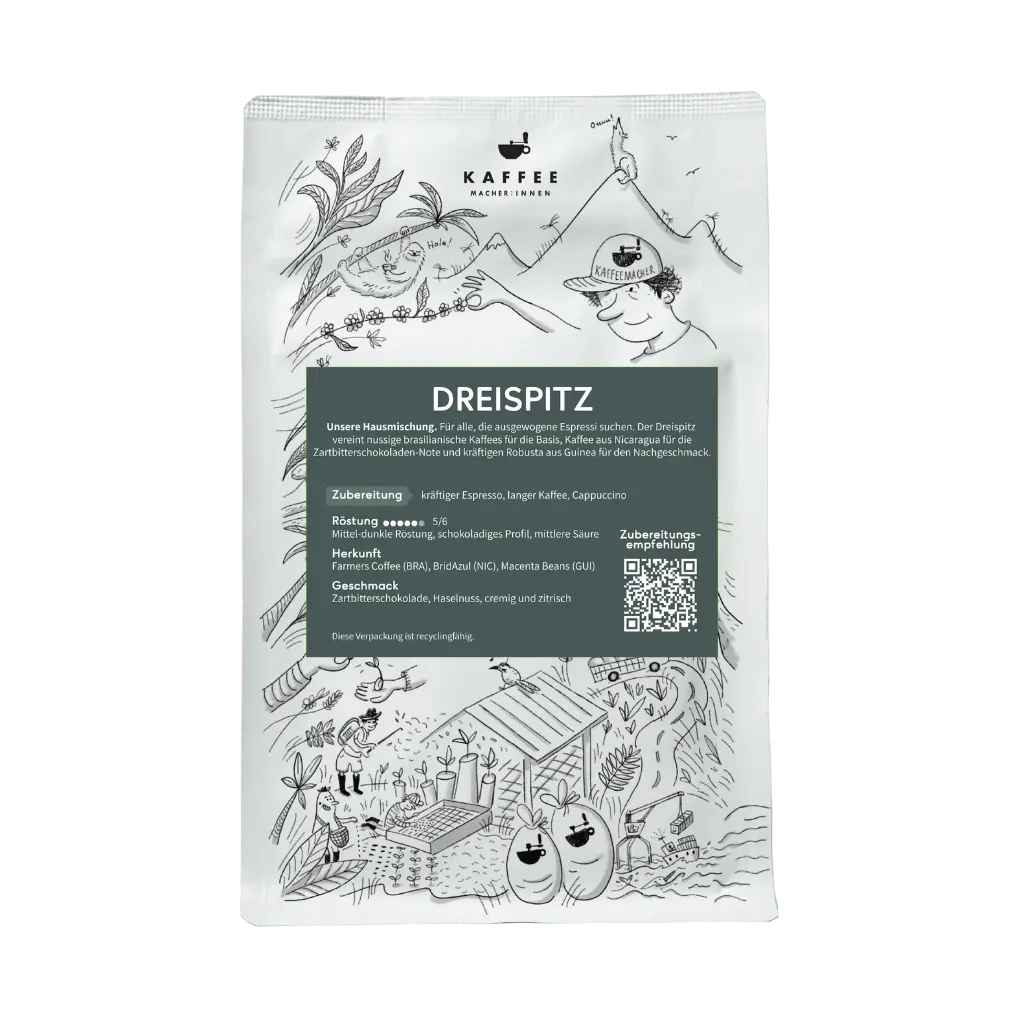

Traditionally, a café crème is a long coffee brewed from a fully automatic coffee machine, sometimes diluted and balanced with cream. More on the history of café crèmes can be found below. In 2015, in collaboration with the Swiss Coffee Association CafetierSuisse, we wanted to find out which café crème consumers enjoy most. To this end, we invited consumers, restaurateurs, and coffee sensory experts. A total of 40 volunteers blind-tasted five different café crèmes as part of Coffee Day at the Kaufleuten coffee shop under the patronage of CafetierSuisse.

Context of the tasting

Of course, both semi-automatic espresso machines and fully automatic coffee machines are technically capable of brewing exceptionally good café crème/nature. However, if you compare the two best brewing recipes from the tasting with the recipes commonly used in the restaurant industry, they differ significantly. And another interesting detail: the better the café nature, the less coffee cream makes it better. The tasting conducted by CafetierSuisse in cooperation with the coffee makers clearly demonstrated this, too.

Experimental setup

The coffees were brewed using different brewing ratios and machines. The water-to-coffee ratio was particularly varied. The grind was chosen so that all beverages were brewed in 25 to 30 seconds. Participants rated the taste, body/mouthfeel, aftertaste, and overall impression (see tasting questions in the box).

After tasting the pure coffee, coffee creamer was added to each cup. Consumers were then asked again whether they perceived the coffee to be better or worse.

The criteria of taste evaluation – what we asked

- Taste : How would you rate the taste of the coffee? Please consider both the aroma and the flavor notes, as well as the balance between sweetness and acidity.

- Body/Mouthfeel : How does the coffee fill the mouth? Is it watery (rated lower) or thicker (rated higher)?

- Aftertaste : What remains of the coffee's flavor and body? If the aftertaste is overly bitter or acidic and unpleasantly tightens the mouth (astringent), then rate it lower. Is the aftertaste pleasant (rate it highly)?

- Overall impression : How would you rate this café crème taking into account its taste, body and mouthfeel?

- Each on a scale of 1 – 10.

The results of the tasting

The tasting results are telling in many ways. While cups 3 and 4 were enjoyed by most test subjects, cups 1, 2, and 5 fell significantly short.

Cup #3 – the daily winner

The day's winner goes to Cup 3 (6.4 points). Brewed with 15 g of coffee and a beverage volume of 115 grams, it is also the strongest cup. It was described in the tasting sheet as well-balanced and aromatic. The consistency was described as full, soft, and pleasant. The testers also agreed on the crème. Two-thirds of the testers found Cup 3 better without the addition of any crème. For the record: the strength of this coffee is 2.4% TDS. This means that this coffee consists of 2.4% dissolved coffee particles compared to 97.6% (for an explanation of TDS and strength, see the article "The Potential in the Bean," cafetiersuiss/Hohlmann, April 21, 2016).

| Cup 1 | Cup 2 | Cup 3 | Cup 4 |

Cup 5 |

|

| Amount of coffee in g | 9 | 9 | 15 | 13 | 11 |

| Drink quantity in g | 115 | 110 | 115 | 125 | 125 |

| Measured TDS |

1.2 | 1.53 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 1.45 |

| Calculated extraction |

17.25 | 19.38 | 20.43 | 18.23 | 17.07 |

Cup 4 – very good at #2

(6.2 points). With 13 grams of coffee per 125 ml drink and a TDS of 1.8, this coffee is the second strongest in the field. The coffee was described as pleasant, round, with a light acidity and bitterness. Some liked the body, while others perceived it as a bit too watery.

Cup #1, #2 and #5 – thin, flat and boring

Three cups yielded very similar results. Cup #1 (4.7), Cup #2 (4.6), and Cup #5 (4.8) were described as watery, tea-like, flat, and bland. They all scored poorly in quality (4.0), particularly in terms of body and mouthfeel. They also shared another characteristic. While 68% of testers found Cup #3, the best cup in the tasting, to be better without cream, the ratio was reversed, on average, for Cups #1, #2, and #5. 65% found Cup #2 to taste better with cream, and 82% of testers rated the body and mouthfeel better with cream.

Summary, conclusion and recommendations

Looking at the brewing ratios and ratings of the best and worst cups, the conclusions are clear. The coffees rated best were those with the highest dosage, 13 and 15 grams per approximately 120 ml of water, and also with the highest strength, i.e., the highest dissolved coffee particle count. The best cup achieved 2.4% TDS.

The lower-quality cups, which average a TDS of 1.39, were penalized in the evaluation. They were unbalanced in flavor, and their body, in particular, was rated poorly.

The explanation for this is obvious. These coffees, in terms of their water-to-coffee ratio, were placed in the middle of the filter coffee range (1.2–1.5 TDS). However, they lacked sensory structure for a filter coffee, and the customer's expectation of a café nature/crème, in particular, spoiled the impression. The best coffee, with a TDS of 2.4, was significantly different from filter coffee while still maintaining a sufficient distance from espresso, which is in the upper range in terms of strength (7–12% TDS).

It therefore seems advisable to deliberately place Café Nature in a higher strength range, with a higher dosage, so that it clearly distinguishes itself from filter coffee. This offers real opportunities to improve the quality of the product, as stated in the article "Café crème, what is that actually?" (CaféBistro 2016-4, pp. 6-7).

To achieve this, the restaurant industry will have to make significant adjustments and use more coffee per café nature. This is possible with some fully automatic coffee machines, depending on the size of the brewing chamber. With semi-automatic coffee machines, the café nature would have to be brewed using the double filter. Consequently, it would no longer be possible to brew two café natures simultaneously using a portafilter. This would certainly slow down the workflow. However, the result in the cup can justify it.

Café nature and café crème offer tremendous potential. Especially since they are often neglected in the restaurant industry, targeted quality improvements can easily and clearly differentiate oneself in the coffee market and with the customer.

History of Café Crèmes

"A café crème is a coffee from a fully automatic coffee machine. It includes cream, or coffee cream, or at least milk, as the second part of the name suggests," explains Michel Aeschbacher, vice master barista and co-owner of the "Showrösterei" in Aarwangen.

"The crema is also characteristic of café crème, which visually distinguishes it from filter coffee," adds Prof. Chahan Yeretzian, who conducts coffee research at the ZHAW in Wädenswil. "The crema is created by a foaming nozzle specific to fully automatic coffee machines."

When examining the origins of the café crème and its name, these two interpretations repeatedly emerge. What both interpretations have in common is that the history of the café crème is directly linked to the history of the fully automatic coffee machine in Switzerland.

From the Muba to the world

Strictly speaking, it's a success story that began in 1985 with the introduction of the first fully automatic coffee machine for home use at the MUBA. Inventor Arthur Schmed created a machine that was the first to perform a complete brewing process, from grinding to finished coffee, at the touch of a button, yet fit comfortably in a home kitchen. Under the Solis label, 5,000 of this coffee machine were ordered at the MUBA. Thus, the counterpart to the first commercial coffee machines, which Schaerer, Rex-Royal, and Egro had been developing and testing for around 15 years, was born.

This coffee machine was a breakthrough: It reduced the effort of preparing coffee to the touch of a button and simultaneously introduced a completely new coffee beverage to the market. The coffee was brewed using high pressure in a brewing piston, with brewing times of up to 35 seconds (depending on the model, brewing method, etc.) and an average beverage volume of 120 to 220 ml. The sensory result is particularly exciting. The extracted coffee differed, particularly in its mouthfeel and body, from the filter coffee we were used to. It was noticeably more intense than filter coffee, yet its flavor was more closely related to filter coffee than to the compact and thick espresso from our last Italian vacation, which was slowly but surely making its way to Switzerland.

A success story begins

The new coffee beverage quickly gained widespread popularity. Word spread about which Swiss rest stops were now serving "push-button coffee" instead of filter coffee, and long-distance truck drivers became the first brand ambassadors. Numerous coffee machine manufacturers anticipated the demand and began developing new brewing units, hot water systems, and more.

The bottom line is: push-button coffee was revolutionary, the machine ingenious, but the coffee certainly wasn't good at first. Coffee machines weren't yet sophisticated, and the brewing temperature wasn't stable enough. The thermal system within the machine, which also housed the grinder, also had to undergo some development. The result was bitter coffee and the occasional cup with an unpleasant acidity. The solution in both cases was crème, or coffee cream, usually ultra-heat-treated milk with at least 10% fat, which, thanks to stabilizers, doesn't curdle when it comes into contact with the acidity of the coffee. Créme has the property of balancing bitterness and acidity and contributing to a full, viscous beverage. The café crème was born and began its triumphant march among Swiss coffee beverages.

On average, one-third of all coffees consumed in the restaurant industry in 2015 were café crèmes. Depending on the business and customer structure, cappuccinos and espressos follow. At Hiltl in Zurich, around 32% are brewed as café crèmes, while at the café-house Unternehmensmitte in Basel, the figure is 27%. And while café crèmes have become the most important Swiss coffee beverage, Switzerland has long been the global market leader in the manufacture of fully automatic coffee machines. Thermoplan supplies Starbucks stores worldwide from Weggis, and Schaerer assembles coffee machines for Dunkin' Donuts in Zuchwil. Coffee from Swiss coffee machines is sold worldwide thanks to Franke Coffee Systems (Aarburg), Egro Coffee Systems (Niederrohrdorf), Jura (Niederbuchsiten), Saeco (Oensingen), Cafina AG (Hunzenschwil), HGZ (Zurich), Eugster/Frismag (Amriswil), Nespresso (Paudex), Solis (Glattbrugg), and Eversys (Ardon). Within just 40 years, Swiss-made has become as inextricably linked to fully automatic coffee machines as espresso machines are traditionally Italian.

But while coffee machines have evolved and can now brew completely different café crèmes, the qualitative debate surrounding the café crème product has become stagnant. Instead of continuing to research the café crème and defining brewing recipes, resourceful café owners discovered its Italian charm, and espresso became a cult drink.

At the end of the 1990s, Spettacolo began to expand, and the cult Caffè Bar Adrianos was born in Bern. Those who wanted to celebrate coffee installed semi-automatic Italian espresso machines. Online forums emerged in which coffee enthusiasts from the hospitality industry exchanged ideas with a growing group of home baristas about brewing recipes, tampers, and temperature stability. And in 2000, the Swiss SCAE held the first Swiss Barista Championship. Giovanni Meola won, naturally on

a semi-automatic espresso machine.

The market is more diffuse than ever

Sixteen years later, the market is more diverse than ever. New cafes open with espresso machines and wonder why their expensive coffee machines don't automatically spit out perfect coffee. Capsule coffee machines are edging out fully automatic piston coffee machines, promising even more automation and better quality thanks to capsule storage. And fully automatic piston coffee machines are now standardly equipped with a milk foam nozzle, promising latte art and the in-machine barista.

Meanwhile, consumers have become accustomed to the wide range of beverages and order a café crème at the Italian restaurant and an espresso at the bar equipped with a fully automatic piston coffee machine. The technological state of new automatic coffee machines offers everything needed to brew a good espresso. However, "automatic" is misleading: A coffee machine that is supposed to brew fully automatically, in particular, needs very good settings and regular maintenance.

Adjustment.

A mill is always a compromise

For a long time, if you order a café crème in a café with an espresso machine, "lungos" were brewed. The same grinder and grind size were used as for espresso. The increased amount of water pressed through this ground coffee, resulting in a very bitter coffee drink due to the increased grinding. Trying to prepare two different beverages with one grinder setting always ends in a compromise. Either the espresso is watery, or the lungo is very bitter. For about five years, the trend toward using a second grinder has been a welcome development. Using a coarser grind than for espresso allows the water to pass through the ground coffee more quickly, preventing over-extraction.

Time for perfect café crème

Fully automatic piston coffee machines can be controlled more precisely than ever before. Next to the semi-automatic espresso machine, there's a second grinder. These are the perfect tools for brewing excellent café crème. Only one thing is missing, both here and there. A qualitative examination of this exciting beverage. We should start discussing how to prepare a perfect café crème, just as the Italians have done with espresso for decades. We should start collecting data on the ratio of water to coffee we use to brew café crème, at which water temperatures, and with which extraction times. At what TDS does café crème taste particularly delicious, and what extraction rate is appropriate (see also the article by Benjamin Hohlmann, Café-Bistro 2016-2)? Which coffee varieties and roast profiles are suitable?

With our fully automatic coffee machines, we now have as much of a presence on the global market as Italian espresso machines. This means we have the tools to allow our most important national coffee specialty, the café crème, to compete in the espresso weight class.

The potential is enormous. Only one thing is in danger: the second part of the name. Because the better the café crème becomes, the more balanced it is. And the more we can, in good conscience, do without the crème.

![]()