The coronavirus is hitting the coffee chain even where we can't see it. We report on the situation in northern Nicaragua and what consequences are looming. In short: things are getting bleak.

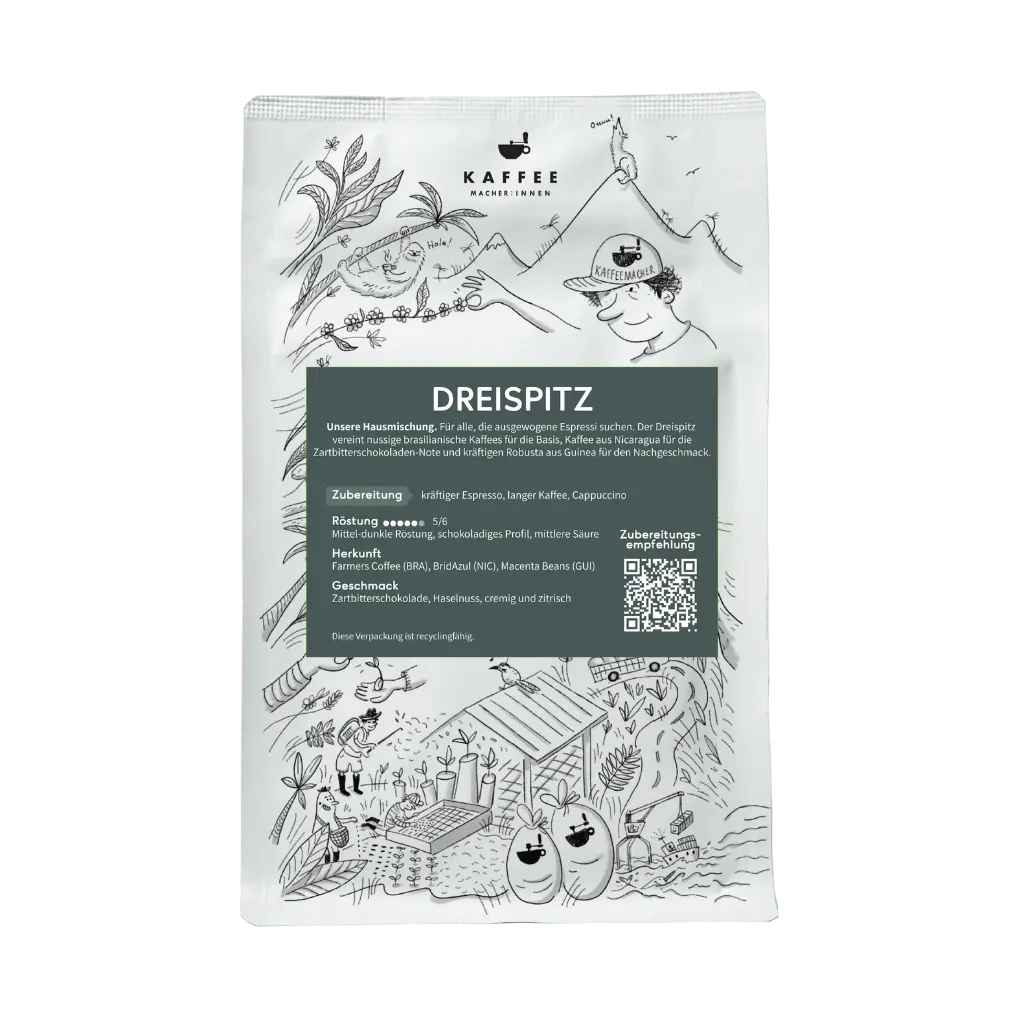

Our coffee from Finca Santa Rita would actually be hulled, sorted by size, and cleaned of defects. Our team would pack it into bags and transport it by truck to the port of Corinto on Nicaragua's west coast.

But right now, everything looks different: the coffee is still unsorted in the warehouse in Ocotal, unhulled and unpackaged. The warehouse is operating at minimal capacity, and coffees are only being tasted in the laboratory. Tim Willems, our farm manager in Nicaragua and founder of BridAzul, the dry mill, told me:

We had to send almost all of our employees home. I can't yet say whether it was a good decision, but it felt right.

Tim Willems

"Social distancing in a coffee shop is almost impossible," says Tim. Lifting heavy bags, sorting coffee in a group, and bottling it—all of this is unrealistic without physical contact or maintaining a two-meter distance. Ultimately, the health of his employees took precedence , and he no longer wanted to offer work that would put employees at risk. Many families, across multiple generations, live in very small spaces. The risk of infection within families is very high in rural areas.

In addition, the health system in Nicaragua is very weak, and COVID-19 is also affecting Nicaragua, even though the government is reporting only 10 infections and two deaths . If you don't test, you won't find any. At the same time, however, cases of pneumonia are rising dramatically, many of them fatal.

In Nicaragua, dark theories are once again circulating on social media, and everyone is accusing the government of a terrible cover-up: Pneumonia just happens, and coronavirus could be prevented. If coronavirus is the cause of deaths, then the problem is home-made. If it's pneumonia, then it just keeps happening.

Day laborers do not work from home

Our partners' decision to temporarily send their employees home was difficult. They knew their employees needed to earn money and many would be looking for odd jobs. Nevertheless, our partners wanted to protect their employees and send them home. It was a difficult decision. They are now trying to provide support in the form of food.

Wage advances are currently virtually impossible because the coffee hasn't been sold yet and the past few months have swallowed up a lot of capital. Emergency parachutes like those currently being distributed quickly and unbureaucratically to companies in Switzerland, Germany, or Austria aren't available everywhere. Not even in Nicaragua. We, as partners, are now more in demand than ever.

The coronavirus pandemic is not only highlighting differences in how people are handling the crisis, but also structural and social inequalities. Day laborers cannot continue working from home. The government in Nicaragua is resorting to the vocabulary of class struggle, shouting loudly: "Only the rich stay at home!" They are even said to have said before Easter week that people should take a break from all this coronavirus talk and go on a beach vacation. The government is also inviting people to demonstrations for health and against coronavirus – people are taking to the streets in droves.

The finca as a retreat

Tim and his local team manage two farms, Finca Santa Rita and Finca el Arbol. Most of the employees would return to their villages, but a reduced team would remain on the farm to keep it running. At the end of the day, a coffee farm is a farm; there's always something to do.

It's quiet on the finca then, and you don't notice anything. However, there's work to be done right now that's almost impossible to complete on time with a small team alone.

Difficult harvest 2019/20

Last year's harvest, which was supposed to be on the ship soon, was difficult. A long dry spell in large parts of Central America shortly after blossoming caused the cherries to grow unevenly. The seeds in the cherries, which later become coffee beans, sometimes developed poorly or not at all.

From southern Mexico, through Guatemala, Honduras, to Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama, yields fell by between 10 and 40% due to the drought. This is massive. Several dealers have reported to us that even average-quality Honduran beans were selling for a price that would normally be fetched for a microlot.

Status Santa Rita

At Santa Rita, we have experienced a loss of approximately 35% in exportable coffee compared to last year. This is due, on the one hand, to the aforementioned drought and, on the other, to our renovation program.

We've been renovating the farm piece by piece since 2017. We're thinning the plantation, first pruning very old trees. If they don't sprout vigorously the following year, we remove them as well and thin the stand to approximately 1,100 trees per hectare. Now, some of the old trees haven't responded to the drastic treatment and have been removed. Because if the input (fertilizer and labor) for a plant exceeds its output, then it has to go.

Next year, the yield on Santa Rita will be even lower because we've just thinned the trees again. However, we expect the first harvest from 1,000 Variedades, which should yield about 10 bags.

No access to fertilizers and pesticides

Since the political unrest began in Nicaragua two years ago, the local currency has depreciated sharply, and imports have suddenly become more expensive. Nitrogen, for example, on which synthetic fertilizers are based, has become between 30 and 40% more expensive.

The majority of fertilizers in northern Nicaragua are imported from Honduras, but now the coronavirus pandemic has added to the mix: the border with Honduras is closed. Anyone who needs fertilizers or pesticides now faces a huge problem. The shortage has caused prices to rise dramatically again. But if fertilizers aren't applied now, the next harvest will be smaller. It's a vicious cycle.

Those who focus on organic farming methods are somewhat less affected in this regard, provided the inputs can be produced on the farm itself. However, this requires a great deal of know-how, which is only available in isolated cases, and exchanges with experts who are currently not traveling.

Had some luck

In January, our team planted large areas of Canavalia, also known as jack bean. This vine species has large leaves and spreads across the ground like a mesh. The reasons for the planting were:

- Large leaves cover the ground =

- less irritation from UV light

- less water loss

- less erosion

- drastically reduced weed growth, which could compete with the plants for food

Canavalias are also powerful nitrogen fixers. They store nitrogen and slowly release it back into the soil. Especially in times when nitrogen-based fertilizers are difficult to obtain, Canavalias and other nitrogen fixers can provide some relief in times of need.

What now?

Forecasting the coffee situation is difficult. Information is fragmented, and communication from the government is almost nonexistent.

But what we do know is this:

- The coffee export of our coffees is not yet foreseeable – we cautiously expect the coffees to arrive in October

- Many producers cannot invest in the farm because they

- could produce less coffee

- and of which fewer could sell

- which will lead to a smaller harvest next year

- the import of fertilizers and pesticides is severely limited

A few months ago, we defined the future direction of Finca Santa Rita. We want to produce organic coffee and become as independent as possible from external inputs. The current situation strengthens our resolve, demonstrates the urgency, and motivates us – even though and because we know that the coming months in Nicaragua will be very difficult.

We'll discuss what the coronavirus means for the coffee chain in this webinar on Sunday: Coffee & Corona. Challenges, Opportunities, Change.