At the mention of the fungus with the botanical name Hemileia vastatrix, people shrug. Roya, coffee rust, or coffee leaf rust is one of the most serious and feared fungal diseases on a coffee farm, and its outbreaks have devastating consequences. It is responsible for millions of dollars in damage annually, and can even destroy entire harvests. The fatal aspect is that coffee rust can be spread by wind and humans. But first things first.

What is coffee rust?

Coffee rust, or la roya in Spanish or coffee leaf rust in English, is caused by the fungus Hemileia vastatrix and is recognizable by orange pustules on the underside of a coffee plant's leaves. If a leaf has only a few of the round, rust-colored spots, it can function more or less normally. However, if the environment promotes the development of Hemileia vastatrix, it becomes difficult for the leaves to supply the plant with the nutrients it needs. Severely infected leaves subsequently die.

Although the fungus only attacks the coffee leaves, it damages the entire plant. Due to the lack of leaves, the coffee plant's ability to photosynthesize is limited, meaning that in the year of the infection, it can produce up to 50% fewer flowers and, accordingly, fewer coffee cherries due to a lack of nutrients.

A distinction is made between primary and secondary loss

Primary loss refers to the crop loss that occurs in the year following the first infestation. The defoliated coffee bush can no longer provide the plant with sufficient nutrients, and the branches and cherries cannot develop properly.

In the following year, this is referred to as secondary loss, which can be even more dramatic. After an outbreak in the year of the initial infestation, it may appear as if the coffee plants will be able to recover—because they can produce leaves again the following season. However, damaged or dried-out, and thus dead, branches can no longer produce cherries. Studies in Central America have shown that primary loss can be as high as 26%. Secondary loss is even said to result in harvest losses of up to 36%.

Coffee rust disrupts the delicate balance of nutrient supply

Hemileia vastatrix turns entire coffee-growing regions into skeletons, destroying the livelihoods of millions of coffee workers. As if the tragic scale of a coffee rust outbreak weren't enough, the fungus also spreads easily throughout the world.

In the 2012/13 and 2013/14 harvest seasons, the worst outbreak to date, also known as "The Big Rust," global losses rose to $600 million. In other words, over 300,000 people lost their jobs due to poor harvests.

How does coffee rust spread?

The basic requirements for Roya can be explained using a triangle. To create the optimal conditions for the development of the fungus, it requires three elements:

- The right environment . Temperatures of 21-25°C are optimal for the spread of coffee rust, but it also thrives in temperatures of 15-28°C. If a period of rain is followed by a hot and humid period, the conditions are ideal. Coffee rust needs water droplets on the leaves to germinate. Therefore, hot and dry conditions are not a good environment for the development of Hemileia vastatrix.

- The recipient . Coffea arabica, in particular, is the desired host for the fungus. Coffea canephora, as well as Coffea liberica and some varieties of Coffea arabica, are currently still resistant to coffee rust.

- The pathogen r. If the environment is suitable and the host is present, a pathogen is still required. If coffee rust is present in the region, the triangle is complete.

Once coffee rust is present in a region, it spreads incredibly quickly. The most common means of spread is the wind, which can carry the spores for many kilometers. However, it is also spread by birds and insects, as well as by travelers on ships, trains, and even airplanes. At the beginning of the spread of Hemileia vastatrix, the spores were carried by workers on their bodies and clothing, thus spreading from coffee-growing region to coffee-growing region.

On a single centimeter of an infected leaf, one can find up to 120,000 to 150,000 spores – an almost unimaginable number.

Another factor contributing to the spread of coffee rust is the very deep genetic diversity of Coffea Arabica. Most Arabica varieties are derived from Tipica or Bourbon genes, which means they are all susceptible to the same diseases and fungi.

Hemileia vastatrix has the ability to continually adapt to new environments, comparable to flu viruses in humans, and to mutate repeatedly. Many varieties that were resistant until 10 years ago are now susceptible to the existentially threatening fungus. Higher temperatures, increased precipitation, extreme winds, and increased human mobility are some of the factors that have led to this.

Coffee rust. The history. The world map.

The coffee world looked to Asia with panic when coffee rust affected every corner of the Indian Ocean basin in the 1950s. Hemileia vastatrix continued its devastating conquest into West Africa and finally landed in the coffee farms of Latin America in the 1970s, covering entire areas. By 1990, it had spread to every major coffee region. However, with adequate care and resistant varieties, which many farmers began planting, it seemed that coffee rust was largely under control—coffee rust was, so to speak, a manageable nuisance.

Hemileia vastatrix was already present in the jungles of Ethiopia before 1870, the place considered by many to be the cradle of the coffee plant. At that time, hundreds of Coffea species and varieties existed, along with just as many diseases and fungi. However, in harmony with nature and the way coffee production was managed and structured at the time, an infestation of one variety with the destructive fungus or another disease had no significant impact on the ecosystem and prevented a potential outbreak.

High biodiversity can stop coffee rust. But in monocultures, it spreads rapidly.

From the tropical hot and humid weather of Ethiopia, coffee was brought to Yemen by the Ottomans, where it was first cultivated on a large scale. Whether they brought coffee plants and thus coffee rust with them, or just seeds, is not known for sure. It's quite possible that coffee rust never reached Yemen, since Hemileia vastatrix adheres to coffee leaves and is not spread via seeds. In any case, the weather in Yemen was hot and dry, and thus not a good environment for the development of coffee rust and other diseases that cannot survive in this climate. The climate in Yemen was essentially a natural deterrent to coffee rust outbreaks, and so the devastating fungus remained undetected.

From Yemen, Coffea Arabica was spread around the world by the colonial powers of France, Great Britain, and Holland. Thus, favorable weather conditions provided new breeding grounds for the dormant monster. The Dutch brought coffee from Yemen to India and from there, around 1800, to Ceylon, present-day Sri Lanka. Soon after, the Dutch were expelled by the British, who immediately planted extensive coffee fields to earn a lot of money.

Ceylon - a ticking time bomb

Coffee rust was first documented in 1861 in Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon), where warm temperatures and extensive rainfall allowed it to germinate and destroyed the entire coffee crop. By the end of 1880, most farmers had switched from growing coffee to growing tea (this, incidentally, also explains why Sri Lanka is now a major tea nation).

The large-scale coffee farms were all attacked by coffee rust. Billions of the fungus' spores rose into the air and were spread throughout much of the world by air currents, by people and shipping, by birds and insects, and, above all, by the wind. By the 1950s, coffee rust had spread throughout the Indian Ocean basin—except for Yemen. Coffee rust contributed to the (temporary) decline of coffee production in Asia and the Pacific. While these regions accounted for one-third of total production at the beginning of the 19th century, 100 years later, it had fallen to just 5%.

The epidemic began in West Africa in the mid-1950s to the mid-1980s and was first discovered on a farm in Bahia Brasil in 1970. From there, it spread and arrived in Central America in the 1970s. Discovered in Nicaragua in 1976, Hemileia vastatrix had reached almost every corner of Central America by the 1990s.

The 3 phases of coffee rust outbreak

The history of coffee roasting is historically divided into three phases.

The first phase , the colonial phase, lasted from 1869 to approximately 1945 and included the first major coffee rust outbreak in the Eastern Hemisphere. During this phase, the spread of the fungus Hemileia vastatrix was driven by the mobility of the colonial powers and their exchange of slaves for harvest labor.

The second phase , the developmentalist phase, describes the period from approximately 1950 to 1990, marked by World War II and the Cold War. During this time, the global coffee trade was largely regulated by the International Coffee Agreement (IAC). To keep prices relatively high and stable, the IAC set export regulations for each country. States assumed a larger role in the marketing of their national coffee than they did during the colonial period. For example, they supported farmers with technical and financial resources and promoted social and political stability through various development projects.

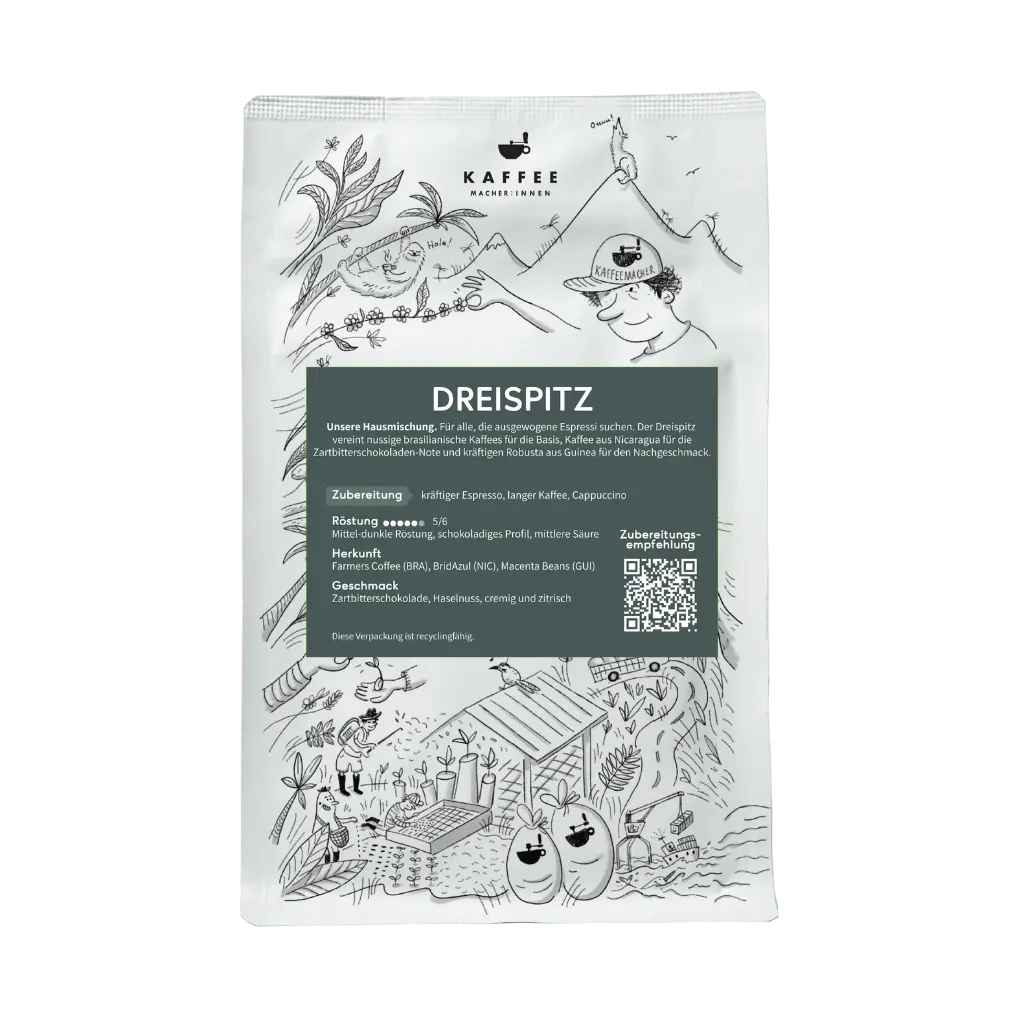

Global distribution of the coffee rust, 1952. This map also reflects the global distribution of Arabica and Robusta coffee at the time. Most countries east of the line produced Robusta, while those west of the line produced Arabica. Coffee Areas of the World in Relation to Rust Disease. 1952. Foreign Agriculture 16:160.

Published in: Stuart McCook; John Vandermeer; Phytopathology® 2015, 105, 1164-1173.

Copyright © 2015 The American Phytopathological Society • DOI: 10.1094/PHYTO-04-15-0085-RVW

The third phase , also known as the neoliberal phase, describes the period from the late 1980s to the present. An incredibly destructive series beginning in Colombia is known as The Big Rust, which reached its negative peak in the 2012/13 and 2013/14 harvest seasons in Central America.

In 2008, Colombia produced 31% less coffee than the previous year. The epidemic spread northward through Central America to Mexico, then moved south again, finally reaching Peru and Ecuador in 2013/2014. The International Coffee Organization estimates that coffee production in Central America cost more than $616 million in the 2012/13 and 2013/14 crop years.

Unlike previous outbreaks in recent decades, Big Rust was not triggered by a carrier brought into an area where coffee rust had previously not existed. Rather, it was driven by extreme weather conditions that favored the development of the fungus.

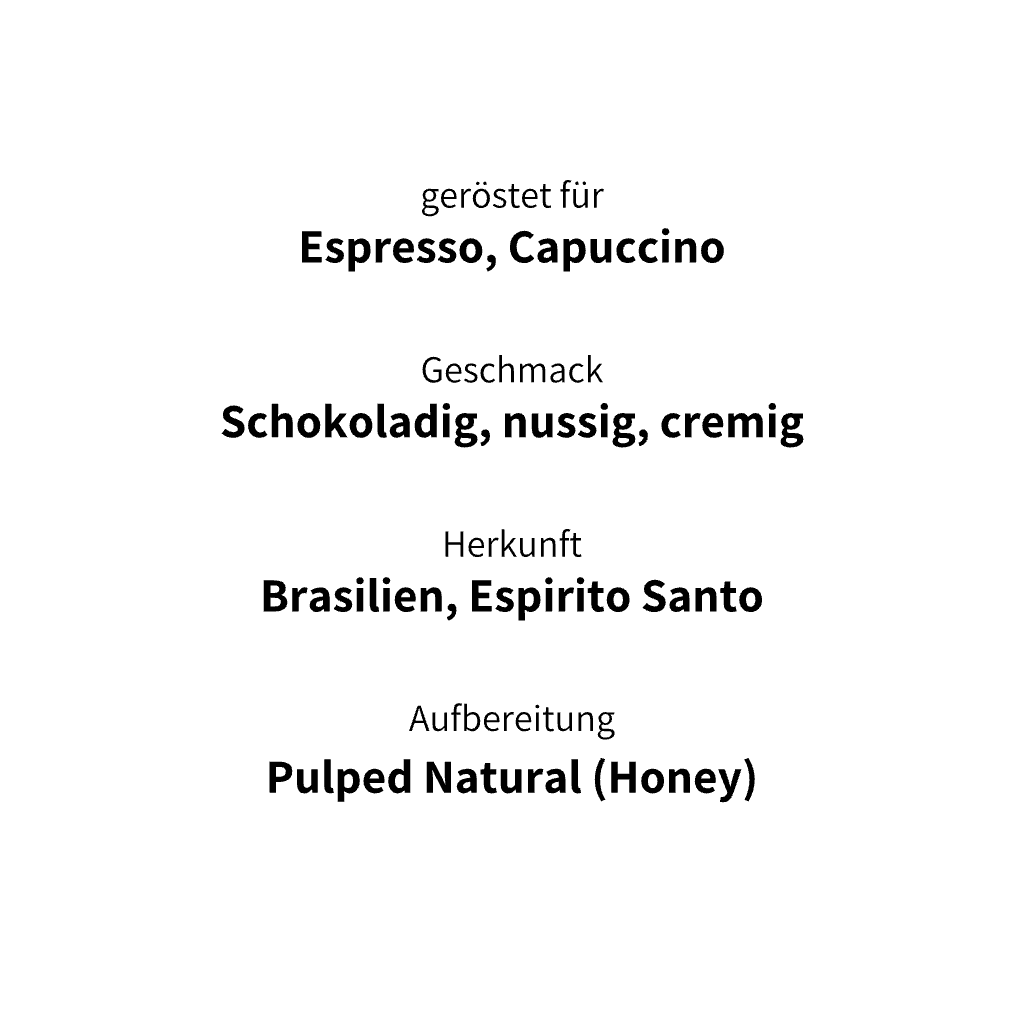

The “Big Rust” in Latin America since 2008.

Published in: Stuart McCook; John Vandermeer; Phytopathology® 2015, 105, 1164-1173.

Copyright © 2015 The American Phytopathological Society • DOI: 10.1094/PHYTO-04-15-0085-RVW

Conclusion Coffee rust

Hemileia Vastatrix always adapts to new circumstances

The ecosystem and the economy are in constant flux, and so is the coffee rust, which, like flu viruses, is constantly mutating. This means that living with Hemileia Vastatrix is always a snapshot in time and can change at any time. For example, it's getting much hotter in the higher regions these days than it was just a few years ago. While our partners at Finca El Arbol used to have daily highs of around 25°C at Easter, the hottest time of year in Nicaragua, temperatures today rise to 35°C or higher.

Unstable stock market - catalyst for Roya

Added to this are the challenges of the stock market, which keeps prices unstable and makes long-term planning impossible. If prices are too low and the coffee farmer cannot cover his costs, let alone invest in renewing coffee plants, maintaining the coffee farm, or combating Hemileia vastatrix or diseases, he must abandon his farm. The land becomes overgrown, and coffee rust spreads unchecked.

Roya increases the cost of coffee production

The control of Hemileia Vastatrix has massively increased the cost of coffee production. With low prices, farmers cannot afford the control and are forced to abandon their farms, leave the countryside, and build a new life elsewhere.

Roya shaped the coffee world as it is today

While coffee rust only marginally reduced the global coffee supply, it shaped global trade in other ways. After 1900, the Dutch invested in the development of the resistant species Coffea canephora , which soon rocked the global coffee scene and today accounts for approximately 40% of coffee production. The plant, originally developed as a response to coffee rust, transformed and shaped the structure of global coffee production and consumption in the 20th century. But more on that another time.

Further reading

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gnPChFLHWA4

https://perfectdailygrind.com/es/2021/01/13/roya-del-cafe-por-que-es-nociva-y-como-controlar-su-propagacion/

https://apsjournals.apsnet.org/doi/10.1094/PHYTO-04-15-0085-RVW#fig1

Stuart McCook, 2019, Coffee is not forever