Not all milk is created equal. There can be a world of difference between one milk and another. And we're not talking about taste, fat content, or price, but rather about its impact on our environment.

In our cafés, more than 70% of coffee drinks are prepared with milk. That's about six times more milk than coffee. For this reason alone, milk is just as important to us as coffee.

Are we allowed to drink milk? This question is a good starting point for a thorough ethical discussion. This article will focus less on ethics, animal welfare, or nutritional physiology (further relevant links can be found at the end of the article) and will instead focus primarily on its impact on the climate.

To this end, we want to present two perspectives. One leads to the conclusion: cows are climate killers. The other paints a different picture. But why does cow's milk have such a high social status, and why is the climate impact of cows on global emissions so high?

What is milk?

Milk is always produced when a mammal gives birth. Without offspring, there is no milk. When we drink milk other than mother's milk, we are always drinking the milk of an infant. So without a lamb, there is no sheep's milk, without a puppy, there is no dog's milk, without a baby, there is no mother's milk, and without a calf, there is no milk. Cow's milk is so important <1> that it is the only milk that does not require the animal species to be named. This is also enshrined in law: in trade within the EU, only milk from cows may be called "milk."

After lactation (suckling), lactase production normally ceases in all mammals. Without lactase, milk proteins can no longer be broken down, and thus milk can no longer be processed in the body. Humans are the exception. They are the only mammal that can continue to consume milk and dairy products after infancy. Approximately one-third of the world's population is now lactose intolerant. How does this happen?

A new study explains: The keeping of livestock began as soon as people became sedentary. Milk was reserved for their offspring. Especially during times of famine, people were then forced to resort to animal milk. In times of malnutrition and deprivation, intolerances usually led to death, and thus the "lactose-tolerant" animals prevailed. Thus, cattle gradually evolved from working animals to farm animals.

Starting in the 1960s, talk of factory farming as we know it today began. At the time, the term promised security of supply and had a positive connotation.

Currently, there are approximately 950 million cattle <2>, of which approximately 260 million are dairy cows <3>. Per capita milk consumption in Germany in 2022 was 46.1 kg (the trend is downward) <4>.

status quo

A look at the list of the most climate-damaging foods shows that the top three places go to cows, butter, beef, and dairy products (cream, milk, and cheese). <5> It's easy to conclude that a world without cows would be a better place.

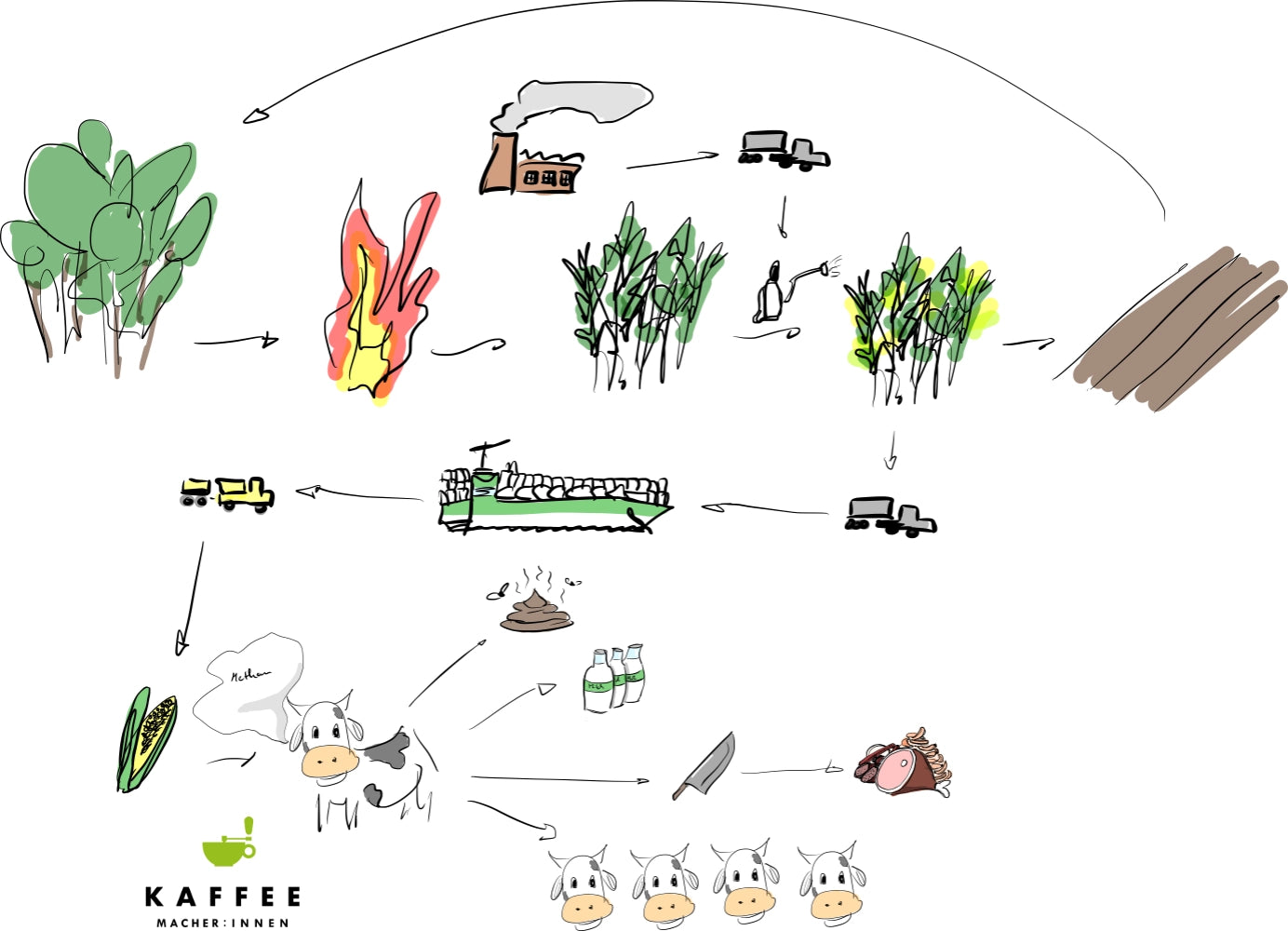

The milk system

Conventionally produced milk (and dairy products) perform particularly poorly in terms of climate impact. The cultivation of concentrated feed, which is largely imported from overseas, causes deforestation and releases large amounts of stored carbon. The monocultures cultivated require large quantities of fertilizer. Fertilizer production is resource-intensive and generates large amounts of CO₂. The application of this fertilizer can produce significant amounts of nitrous oxide. (Nitrous oxide is particularly harmful, as it has 300 times the climate impact of CO₂.) Transporting the concentrated feed to Europe produces additional CO₂. The stored nitrogen also arrives in Europe with the transported crops and over-fertilizes the fields in the form of cow dung. This leads to leaching in cultivation and over-fertilization in Europe. Both lead to measures that result in more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. A vicious circle for the soil and the climate.

In addition, the cow itself produces large quantities of methane (approximately 550 liters per day) during the processing of food, which is approximately 28 times more harmful to the climate than CO₂. Thus, methane emissions from "the cow" are responsible for approximately 48% of agricultural emissions in Germany in 2022.<6>

Depending on the type of husbandry, 0.9 kg CO2e (organic pasture farming, with allocation of meat sales) to 1.64 kg CO2e (conventional farming without pasture, without allocation) <7> are produced in Germany, but the global average is 2.4 kg CO2e per liter of milk <8>.

The emissions (global average) are approximately the same as those produced by burning one liter of gasoline. (Tank-to-wheel analysis → i.e., combustion alone, without recovery)

Is 1 liter of milk as harmful as 1 liter of gasoline?

Are there any solutions?

There are various approaches, from increasing milk yield to feed additives that reduce methane emissions. <9>

One solution would be to increase milk yield while maintaining methane emissions. 100 years ago, a cow's milk yield was around 2,000 liters per year; today, it's around 8,000 liters. (These figures are for cows bred for milk production. For dual-purpose breeds, the figures are lower. For our dairy farmer, for example, the cows produce around 4,000 liters per year.) If you convert a cow's daily methane emissions, approximately 550 liters (which in turn corresponds to approximately 400 grams), into annual milk yield,* milk 100 years ago had a footprint of 2.05 kg CO₂ equivalents, compared to 0.51 kg CO₂e today. If you add feed additives, which promise a one-third reduction in methane, the figure would be just 0.34 kg CO₂e. That would correspond to a reduction of almost 84%. However, this approach often makes a mistake: it only considers the output.

A cow 100 years ago most likely ate only grass from the pasture, whereas today's cow must be fed the concentrates described above to achieve such performance. The feed additives also have to be manufactured, processed, shipped, and added to the feed.

Is the cow from 100 years ago likely more sustainable? And perhaps the solution lies not in technological progress, but in the way animals are kept?

The climate killer… or not?

Many people view the cow as a milk-producing machine, and their emissions, like those of machines, are passed on to the final product. These machines can be optimized, increasing output and reducing emissions. All of this is technical optimization for a living being. We would like to present another perspective.

Change of perspective

Every human being emits CO₂. Just like cows, we metabolize our food and emit CO₂ (and methane) in the process. This may only be a small part (between 168 and 2040 kilograms of carbon dioxide per year; <10>

Comparison of the CO₂ equivalents of methane from dairy cows and CO₂ from humanity

Assumption 1: 8 billion people; each emits an average of 1.1 t CO₂ per year through their breathing

Assumption 2: 260 million dairy cows; each emits approximately 400 g of methane per day; the greenhouse effect of methane is 28 times greater than that of CO₂. Thus, the average CO₂e emissions from methane excretion are 4.1 t CO₂.

According to this, humanity emits 8.8 billion tons of CO₂, while dairy cows emit "only" 1.07 billion tons of CO₂e through their methane emissions. (If beef cattle are included, emissions would be 14.98 billion tons of CO₂e.)

(The breathing of cows and the methane emissions of humans are missing here)

Both our breathing and the methane emissions from cows are part of the carbon cycle. Methane breaks down into CO₂ and hydrogen. This CO₂ is absorbed by plants, which store the carbon and release the oxygen back into the atmosphere.

Cows provide us with proteins and carbohydrates that would otherwise be unavailable. We can digest corn and soy ourselves, but not grasses.

Where do we get our milk from?

We source our milk from Jonas Plattner, a small-scale organic dairy farmer in Reigoldswil, Switzerland.

The yard

- Jonas lets his cows graze on 30 hectares of land

- He owns 15 cows and 1 bull

The cows

- The cows are a dual-purpose breed: they produce less milk but a little more meat when they are older

- Jonas' cows live to be about 15 years old, which is very old in milk production

- the bull is part of the cow herd

- the cows give milk twice a day, a total of about 10l per cow

- In one week the cows produce about 900l

The food

- The cows eat only grass, in winter hay

- Concentrated feed such as soy or corn is not used, Jonas also does not use silage

Attitude makes the difference - Regenerative Agriculture

We all know that trees bind CO₂. Even more important for our climate are the soils: forest soils, meadows, and moors. Technical solutions in the fight against global warming mimic what nature has already solved.

With factory farming, more and more animals were kept on ever smaller areas. This allowed the remaining land to be used to grow feed. As described above, however, this leads to depletion in some areas and over-fertilization in others.

But when the cattle return to the meadows, they can provide additional carbon sequestration, making these pastures, which are unsuitable for arable land, available for human consumption. For ideal carbon sequestration, they must be kept in small, frequently spaced grazing areas, allowing them to be grazed and fertilized with cow manure (mob grazing). Afterward, this area is left undisturbed for a certain period of time to recover. This promotes root growth before the cattle are allowed to graze it again.

No grassland without grazers.

If you compare the carbon sequestration that can occur with the emissions, the overall impact of cows looks completely different. Unfortunately, there are few studies on this. One of them is from "White Oak Pastures," <11> which concludes that for every kg of meat, approximately 1.6 kg of CO₂ is stored in the soil.

Conclusion

Back to milk. It's in our hands; we can choose for our needs at home: Do we support the status quo, choose alternatives like oats, or opt for the renewable option? Two out of three options tend to have positive climate effects. That sounds good. (But the fact is, the actual proportion is (still) small.)

In Germany, there are around 100 farms that produce milk not only regeneratively but also through mother-calf husbandry. What's special about this is that the calves grow up with their mothers and are allowed to drink first, while humans take what's left over. The organic share of all milk produced is approximately 3.5%, of which approximately 2% is mother-calf husbandry. <12>

As citizens we reject factory farming, but not yet as consumers.

Further links:

- TED Talk Allan Savory

-

TED Talk Bobby Gill

- Farm Rebellion on Disney+ - Trailer

- NDR Green Garage - Enjoying beef without guilt?

- The Milk System on Netflix - Trailer

- ARTE documentary: What can we still eat?

Books

- Cows are not climate killers! - Anita Idel

- Rebels of the Earth: How we save the soil—and thus ourselves! - Benedikt Bösel

- Holistic Management Handbook - Allan Savory

Sources:

<1> cf.: statista.com, Milk - Germany , as of 28.09.23

<2> cf.: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/28931/umfrage/weltweiter-rinderbestand-seit-1990/ , as of 28.09.23

<3> cf.: agrarheute.de, Dairy farming XXL: Herd size is growing worldwide , as of: 28.09.23

<4> cf.: tagesschau.de, Why Germans drink less milk , as of 28.09.23

<5> cf.: utopia.de, These 6 foods are the worst for the climate , as of 28.09.23

<6> cf.: umweltbundesamt.de, Contribution of agriculture to greenhouse gas emissions , as of 28.09.23

<7> cf.: Federal Environment Agency,Making hidden environmental costs of agriculture visible using the example of milk production systems , as of 28.09.23

<8> cf.: bauernverband.de, Methane emissions in cattle farming , as of 28.09.23

<9> cf.: dsm.com, The proven solution for methane reduction , as of September 28, 2023

<10> cf.: co2online.de, What does a person breathe out ?, as of 28.09.23

<11> see: whiteoakpastures.com, Study: White Oak Pastures Beef Reduces Atmospheric Carbon , as of September 28, 2023

<12> cf.: ardmediathek.de, Contents , as of: 28.09.23