Supermarket coffee is available at dumping prices. How do supermarkets manage to offer such cheap coffee? What's actually in it? And can such coffee even be fairly produced? One thing is certain: if supermarkets improve even a little, it's a lot.

We're often asked if we could test supermarket coffees. No, we don't; that would be far too easy. Simply pointing fingers at big brands wouldn't be productive for anyone. What we can do, however, is try to contextualize supermarket coffees. Why they're so often dirt cheap, why many taste the same, and whether anyone even makes a profit from them.

It's also important to clearly identify the opportunities supermarket coffee can offer—for consumers and producers alike. So we can now ask ourselves:

What is the purpose of supermarket coffee?

Why are the coffees often so cheap?

And what potential do supermarkets have that hardly anyone else has?

The role of supermarket coffees

In many cases, the purpose of coffee in supermarkets is to lure people into the store. Coffee in supermarkets often functions like laundry detergent—when there are special offers. Coffee is often available in value packs and at fixed promotional times that have been planned well in advance.

Taste of supermarket coffee

It should come as no surprise that many supermarket coffees taste very similar. There are two primary reasons for this: First, large quantities of coffees are needed that always taste roughly the same. This limits the choice of countries of origin for the green coffee. Second, and this is the reverse, coffees with more specific flavors rarely make it into supermarkets because they are rarer and, above all, more expensive.

The larger a coffee brand is, the less distinctive its taste is. Because a brand has to keep its promise of always tasting the same. And this is ensured by similar coffees with consistently similar ingredients.

The cheaper coffee becomes, the worse the quality becomes. Coffee is one of the few products that actually tastes worse as the price drops. Expensive coffees don't necessarily taste better, but they can. This is where sensory analysis comes in to determine what distinguishes good coffee from well-intentioned marketing.

Of course, inexpensive coffees that taste like coffee have their place. Not everyone wants coffees that smell extremely aromatic and taste like everything but coffee. However, one shouldn't set one's expectations for sensory delights too high with inexpensive coffees. Quality coffee comes at a price.

What's in supermarket coffee? It's almost always the same.

That may sound a bit bold, as I haven't even tried nearly all the coffees available in supermarkets. Why would I make such a statement? It's because of the price and the customer base a supermarket is targeting.

Supermarket coffees are usually blends. These can smooth out sensory, price, and delivery fluctuations. It's not that many different green coffees bring many different flavors to the supermarket blend; no, they bring stability. And they lower the price.

Supermarket coffees are stable in price and taste. Therefore, coffees that can meet precisely these requirements are needed. Many come from regions where high production is achieved, a large proportion of production is mechanized, and post-harvest processes are extremely efficient.

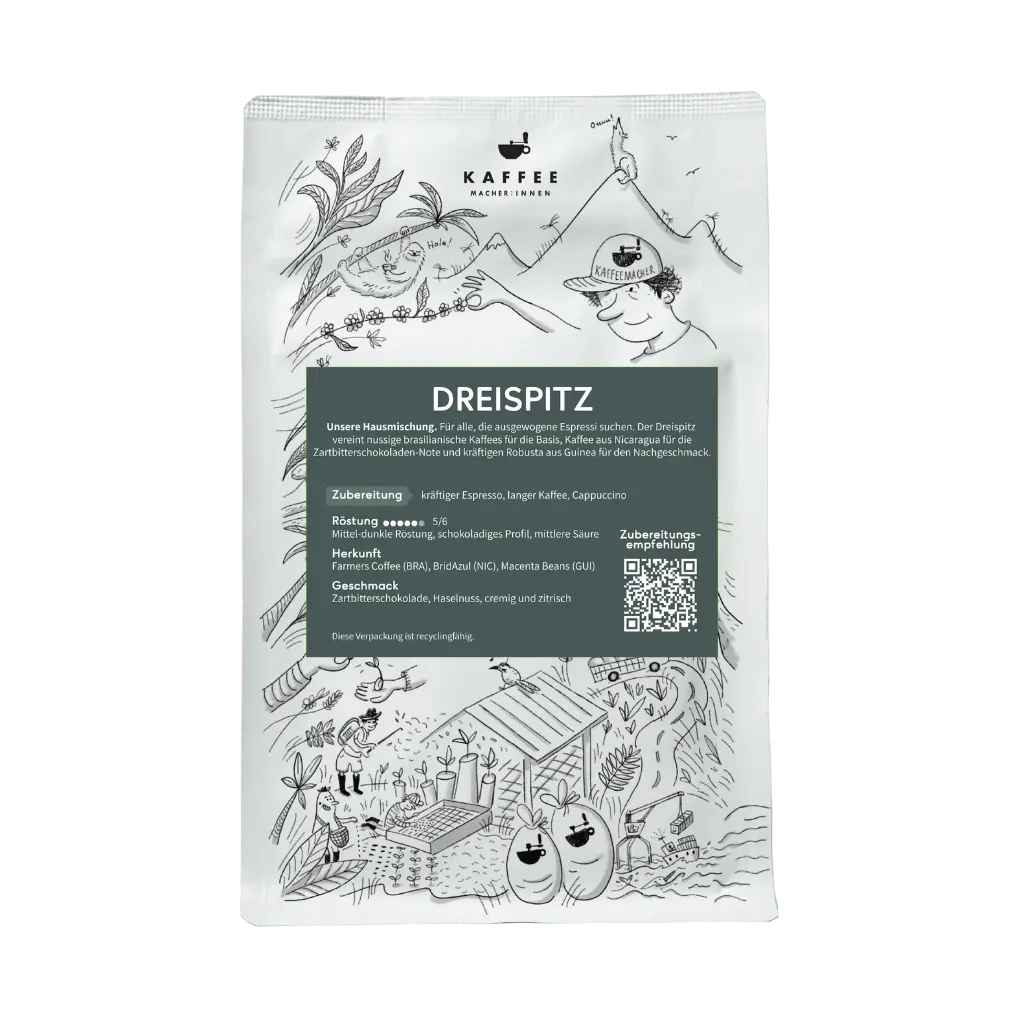

These are – with exceptions – mainly Arabicas from Brazil, Honduras, Peru and Mexico, as well as Robustas from Vietnam, West Africa and increasingly also India.

The most commonly used green coffees in supermarket coffee

A lot of coffee is produced in the countries mentioned, sometimes at extremely low prices which, except in Brazil, have little or nothing to do with the real production costs.

The standard qualities from these origins are available in large volumes and fulfill most of the purposes that supermarket coffee is intended to serve.

But why are some of the coffees in the supermarket more expensive?

This is usually about brand strengthening, not about drastic differences in green coffee quality. A supermarket needs different segments to appeal to different customers. The good thing about this is that someone who buys the premium product is unlikely to buy the cheaper version of the same product. Therefore, the shopping cart rarely contains both the most expensive and the cheapest coffee.

And that's a huge advantage for a supermarket: the difference in blend, or even in flavor, doesn't necessarily have to be the same; a lighter or darker roast might even help. And of course, the packs, which come in different designs, names, and emotions, also come in different heights.

Premium products at eye level, mid-range at belly level, and discount items at knee height. Take a closer look at the coffee aisles the next time you're in the supermarket; they're full of simple psychological tricks.

Why are coffees so cheap in the supermarket?

This is primarily because supermarket coffees are produced in large quantities. Economies of scale and efficiency in roasting, packaging, logistics, and storage ensure lower prices, which can be passed on to consumers. Large roasters are always significantly more efficient than smaller and medium-sized roasters in terms of labor costs.

from our blog: https://kaffeemacher.ch/wer-roestet-wie-kaffee/

Lower prices are often, but of course not always, passed on, because a higher price for supermarket coffee does not necessarily reflect the green coffee quality, but rather appeals to the emotions that a brand can evoke.

The green coffee itself accounts for a small portion of the final cost breakdown of supermarket coffees. The overhead, i.e., the entire operating costs, must be borne by the coffees themselves. This isn't just the case with large roasters, of course, but with every business. However, the distribution is much wider with supermarket coffees because production can be so efficient.

The cheap green coffees

The green coffee beans for supermarket coffees are purchased in bulk. This requires a roastery, and the roastery usually has a trader who organizes the coffees for the roastery. And because the food industry is a low-margin industry, it's all about volume – more volume means more margin. These volume deals are also interesting for trading houses, so they often pass on very good prices to large roasters. At the same time, it's also interesting for large coffee producers, such as very large cooperatives. More volume is sold, albeit at a smaller margin, but this is recouped through the larger volume.

That's buying power. Those who buy a lot are sought after.

Are supermarkets and their associated roasters paying enough for green coffee?

We can't answer that question, but we can speculate. It's best to simply ask customer service what prices were paid for the green coffees in blend X in the supermarket. That could spark an interesting discussion—if supermarkets were to disclose their purchase prices.

But silence prevails here – and not just among supermarkets, but among the vast majority of coffee roasters. Transparency Coffee is trying to counteract this and is encouraging the disclosure of green coffee prices. And does that hurt? No. It's good. That's why we publish our purchase prices. More discussion is needed here.

Do low prices for coffee make sense?

Counter question: for whom? For those who shop – yes. And for everyone else in the coffee chain? For those who produce, deliver, sort, carry, transport, and store coffee on shelves? That remains to be answered.

Basically, and not only for coffee, but for all foodstuffs in particular:

Someone will pay if we don't pay.

The message that coffee has to be cheap is therefore a false one. Coffee has to cost something because all the work behind it costs money. If coffee costs little, then that's not a sustainable approach.

What opportunities does supermarket coffee offer?

The biggest calls for change. Because, do small things make everything better? Absolutely not. Small may be beautiful sometimes, but to deliver on big promises, you need big volumes. And where are those? In the supermarkets.

The market power of supermarket coffee is massive. The roasted coffee market is extremely consolidated, as this impressive graph from the Hivos Coffee Barometer shows. The world's top 10 roasters roast at least 35% of the coffee that is then sold primarily in supermarkets.

And what exactly does this power consist of, besides the fact that prices can be pushed down and accountability is difficult to trace?

The powerful freedom of substitution. Changing coffees when they become too expensive for supermarkets.

Blends, as we discussed earlier, allow a roaster to achieve not only sensory but also financial stability. If one coffee becomes significantly more expensive due to a poor harvest or rising domestic prices due to social unrest, that coffee can be replaced with one that is sensorially similar. For this reason alone, it's hardly worth putting more sensory-interesting green coffees into a supermarket blend.

So it's normal for entire blends to be swapped. That sounds logical, but the consequences are massive. All these effects are far away and not noticeable here—or, in this case, tasteable. If several containers of a coffee X are swapped, it has an impact on everyone involved in production and export.

And this is where supermarket coffee has a great opportunity to make things better

Let's imagine that a roastery that roasts 50,000 tons of coffee annually—that is, an industrial roastery in Germany—imports approximately 3,000 shipping containers full of coffee annually. Each container contains approximately 17 tons of green coffee.

A cooperative in Honduras makes maybe 5 containers a year, 1 of which goes to the roastery in question.

That would be 20% of the cooperative's output, or 0.03% of the roasted output at the roastery. That's almost nothing for the roastery, but a lot for the cooperative.

If the supermarket now decides to price, market, pay for, etc. this coffee in this container differently with this cooperative, then that will have a huge impact on the producers. And for the supermarket, it's low-hanging fruit. In terms of volume, marketing ("our sustainability range," for example), and, of course, financially.

Now, there are supermarkets—albeit on a very small scale—that are taking precisely these approaches. And these projects deserve support. But inform yourself, ask questions, and be critical. How long-term these projects—the name suggests—are intended remains to be seen.

You can find various examples online of supermarkets writing their own coffee stories. This often only applies to a fraction of their coffee range, but it's a start. And it would prove that market power can also be used positively.